Principles of learning and how they apply to training and teaching

| Author(s) |

|

| Reviewers |

|

OverviewQuestions:

Objectives:

What are the main principles that drive learning?

How can these principles be applied to training and teaching?

Describe how learning works according to a few learning models

Explain how learning models can help you improve your teaching in the classroom

List learning strategies and principles suggested by evidence-based research results

Time estimation: 2 hoursSupporting Materials:

Published: Sep 23, 2022Last modification: Mar 11, 2025License: Tutorial Content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The GTN Framework is licensed under MITpurl PURL: https://gxy.io/GTN:T00067rating Rating: 5.0 (1 recent ratings, 1 all time)version Revision: 17

In this tutorial we will discuss the principles of learning

Learning results from what the student does and thinks and only from what the student does and thinks. The teacher can advance learning only by influencing what the student does to learn

H.A. Simon (one of the founders of the field of Cognitive Science and Nobel Laureate)

This quotation from Herbert A. Simon clearly indicates that we cannot talk about teaching, teaching practices or effective teaching techniques if we don’t understand first how people learn.

In this lesson, we want to share with you what we have collectively learnt about how learning works. Our knowledge in the field of cognition and learning comes from diving into pedagogical and cognitive research results, reading books such as “How Learning Works” (Ambrose et al. 2010) or “Small Teaching” (Lang 2021) and many others, studying research articles published in the field of cognitive science and educational psychology, attending instructor training courses (like this one), and - last but not least - from our own experience as both instructors/teachers, learners, and passionate observers of learning processes and teaching practices.

Since this material cannot cover the broad literature on the subject of learning we strongly invite you to commit to read at least one book on how learning works (Ambrose et al. 2010, Lang 2021), have a look at the Software Carpentry Instructor training materials and explore the material available through the ELIXIR Train-the-Trainer course.

Comment: SourcesThis tutorial is significantly based on Via et al. 2020, session one of ELIXIR-GOBLET Train the Trainer curriculum.

How do people learn?

So let’s start with “How do people learn and how does learning work”

General definition of learning

(Relatively) permanent changes in behaviour, skills, knowledge, or attitudes resulting from identifiable psychological or social experiences.

- A key feature of learning: permanence

- The change has to last

- Changes do not count as learning if they are temporary

- Example: learning a phone number

Why is it important to learn about how people learn?

- It is common to confuse our effort (i.e. our teaching) with what learners get from our efforts (i.e. their learning)

- We usually assume learners learnt

- Nevertheless, the distinction between learning and teaching is especially important for teachers to remember and it is essential that teachers become aware of the fact that the way they think about learning affects the way they teach and that the very circumstances of teaching can influence teachers’ perceptions of learning, and therefore also influence how they teach.

- For example, imagine that a cognitive scientist convinced you that people don’t retain anything of what you tell them after 20 minutes of passively listening to you. Would you keep lecturing for more than 20 minutes?

- And how would you teach if, in contrast, you assumed that the mind is a vessel to be filled?

- Moreover, most teachers tend to think that what is taught is equivalent to what is learned, namely that what they teach is the same as what students understand or retain of what they teach (even though most of them know that assuming this is a mistake and that teaching and learning can be quite different).

- Learning how learning works helps clarify this distinction

- The way we think about learning affects the way we teach

- Understanding how people learn makes you a more aware and therefore better teacher

- You can use such knowledge to improve your day-to-day teaching

According the Meaningful Learning Theory, developed by the psychologist David Ausubel, meaningful learning generally arises from a process of learning to learn. He considers that if meaningful learning is achieved, it transcends the rote repetition of unconnected content and allows for the construction of meaning, making sense of what has been learned, and understanding its scope of application and relevance in academic and everyday situations.

Learning metaphors, theories and models

Learning - similarly to thinking - is a complex process that requires multiple approaches spanning many different disciplines, ideas, theories and models to be understood.

Many learning theories, models, concept and ideas from from the Science of Learning, Educational Psychology, and the Cognitive Sciences are relevant to classrooms, in that they describe at least some of what usually happens there and offer guidance for assisting learning.

This session will provide you with some understanding of how learning works but it is far from being exhaustive. In particular, we will present and discuss learning models, concepts and perspectives that are important for you to know as they suggest things that you might do in your classroom to make learners’ learning more productive and your teaching more effective and mindful.

A metaphor is a word from one thematic domain that has been embedded in another one, thus entering a network of new linguistic relations. This is, indeed, what metaphors are all about: they are transplants from one discourse to another. They are a source of new ways of seeing things. “Metaphors of learning” are a source of new ways of seeing learning.

We can use metaphors to shape and reveal our way of thinking about learning and, therefore, shape our actions as teachers.

A mind is a fire to be kindled, not a vessel to be filled

How the mind-as-a-vessel-to-be-filled metaphor may affect your way of teaching? You are likely to spend your time in the class at the blackboard, trying to ‘transmit’ to the students your own knowledge.

- Think about the following metaphors “A mind is a fire to be kindled”. How this metaphors may affect your way of teaching?

- Think about the following metaphors “Teaching is growing a garden”. How this metaphors may affect your way of teaching?

Metaphors define the role of the teacher and the learners

| Metaphor | Teacher | Learner |

|---|---|---|

| Learning is knowledge transfer | Defines, develops and prepares contents | Receivers and memorizes |

| Learning metaphors | Prepares the environment, guides the exploration | Explores, works on information, attributes meanings |

| Learning is participation in social practices | Community that shares activities and social practices | As teacher |

Learning theories

Learning theories describes how students receive, process, and retain knowledge during learning. However, there is no single one theory (as in physics for example). There is a massive catalogue of learning theories out there and there is no universal theory of learning.

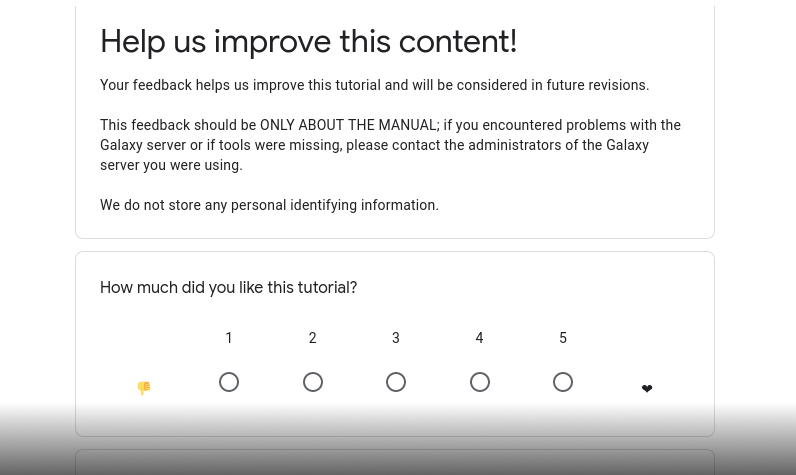

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabPhilosphers and researchers from multiple disciplnes have proposed a large number of learning theories: a flavour of the diversity of approaches and philosophies can be gained, for example, from the HoTEL (Holistic approach to Technology-Enhanced Learning) website. But which should we rely on? Which should we learn, teach and apply?

There is no universal theory of learning, but there are interesting elements for classroom teaching in many different theories There are elements of truth in different theories, and evidence-based research results that support learning principles recognized and applied today. In this sense there are interesting elements for a teacher in many different theories.

In the following sections we will explore the most important learning theories.

Comment: Principal learning theoriesWe will briefly describe the key ideas from each of these perspectives and explain how you can use them in your classroom to support learners’ learning.

Behaviourist Learning Theory

Behaviorism is a psychological movement that posits behavior should be studied as a natural science akin to fields like chemistry or physics. It conceives learning as changes in overt behavior. In this context, learning is acquiring new behaviours by conditioning, reflex response to stimuli, reward/punishment.

An important concept from this theory is operant conditioning, a variety of behaviourism that focuses on how the consequences of a behaviour affect the behaviour over time.

This theory is based on the idea that certain consequences (reinforcement or inhibition of a behaviour) tend to make a behaviour happen more or less frequently. According to the behaviorist perspective on learning, the instructor assumes a dominant role within the classroom, exerting complete control over the learning process. Evaluation of learning is carried out by the teacher, who determines what is considered correct or incorrect.

Cognitivist Learning Theory

Diverse authors agree that, in order to implement adequate online teaching practices, it is necessary to take into account the characteristics of mental processes (Wu et al. 1998, Chandler 2004).

Cognitivism emerged in the 1950s as a response to Behaviorism, which was deemed inadequate in explaining cognition. Cognitive Learning Theory aims to describe the links between cognitive structures -defined as the mental representations of objects or ideas- and the learning process (Qin 2009, van der Veer and Felt 1988), with a special focus on the processing of information. Two important theories derive from this one: Information Processing Theory and Cognitive load theory:

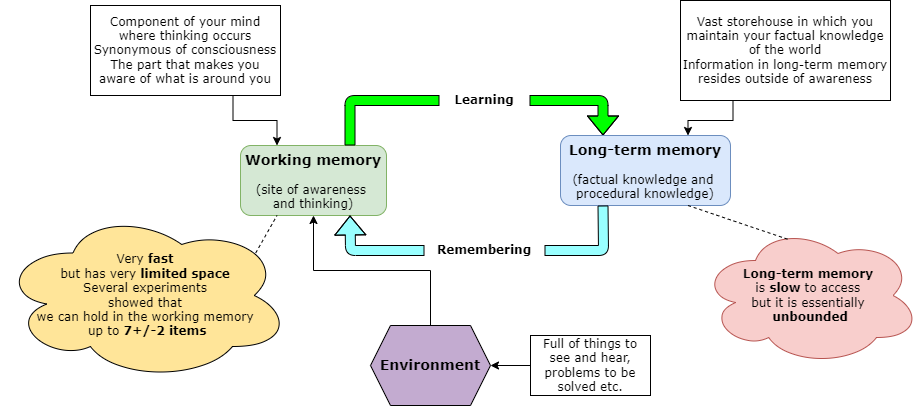

The Information Processing Theory describes learning as the result of sequential processing of information, which involve three types of memory: immediate memory, working memory and long term memory (Gentner and Stevens 2014). According to this theory, adequate learning resources require to assume two key elements: firstly, the fact that working memory is limited; and secondly, that the interaction between working and long term memory plays an important role in the construction and transferability of knowledge (Chandler 2004, Herring 1993, Yilmaz 2011).

On the other hand, Cognitive Load Theory seeks specifically to address the efficiency with which information is processed. It states that the verbal and visual information is processed by independent cognitive structures, both of them with a limited capacity (Forišek and Steinová 2012, Via et al. 2013, Kats 2010, Wright et al. 2010). An interesting concept derived from this theory is the cognitive overload, which refers to those situations in which the information flow exceeds the learner’s processing capacity, resulting in an inhibition of the learning process (Aidi 2009).

Constructivist Learning Theory

Constructivism holds that learning is essentially active; a person who learns something new incorporates it into their previous experiences and their own mental structures. Each new piece of information is assimilated and deposited into a network of previously existing knowledge and experiences (Abbot and Ryand 1999). All these ideas have been taken from different nuances, and two authors stand out: Jean Piaget with psychological constructivism and Lev Vigotsky with social constructivism.

From the perspective of psychological constructivism, learning is fundamentally a personal matter. It maintains the idea that the individual, both through cognitive and social aspects of knowledge as well as affective ones, is not a mere product of the environment or a simple result of his or her internal dispositions, but a construction of his or her own that is produced day by day as a result of the interaction between these two factors. The driving force of this activity would be cognitive conflict; in any constructivist activity there must be a circumstance that shakes the previous structures of knowledge and forces a rearrangement of the old knowledge in order to assimilate the new.

According to the social approach of Lev Vigotsky, learning is that process in which the individual assimilates certain historical-cultural experience at the same time as he/she appropriates it, which requires an active subject who gives meaning to this experience, transforming it into his/her subjectivity (Ruiz Mayra Rodrı́guez and Garcı́a Emilio Garcı́a-Merás 2005).

The aim of Vigotsky’s theory is to discover and stimulate the zone of potential development or zone of proximal development in each student, which is defined as the distance between the actual level of development, determined by the ability to independently solve a problem, and the level of development potential, determined through solving a problem in collaboration with a more able peer (Moreira 1997).

For Vigotsky, cognitive development cannot be understood without reference to the social, historical and cultural context in which it occurs. According to this author, higher mental processes (thought, language,voluntary behaviour) have their origin in social processes; cognitive development would be the conversion of social relations into mental functions (Moreira 1997).

Critical Learning Theory

The Critical Learning Theory, also known as Transformative Learning Theory, aims to define the mechanisms involved in the development of critical thinking during the learning process. It considers that thought must be capable of questioning even the logic of reasoning itself, that is, it must be capable of problematising what has hitherto been treated as self-evident, of turning into an object of reflection what had previously been simply a tool. According to Marcuse 1964, critical thinking aims to define the irrational character of established rationality.

According this theory, learning occurs when the learning process induces a shift in the student’s frame of reference. Although this goal can be achieved in multiple ways, a successful strategy is to stimulate reflection on uncritically accepted assumptions. It is the educator responsibility to cultivate students’ skills related to autonomous thinking by designing activities for that purpose.

Critical Learning Theory emphasises two elements: the importance of the subjective role of each learner in finding meaning for him/herself, and how social and economic conditions constrain and distort the social construction of meaning (Giroux 2004).

- Order the following approaches (from the most to the less effective one) for you when you want to learn something new

- Read about it

- Attend a training session !

- Have a go ?

- Do, reflect, process, further understand?

- Write if you recognise elements of one of more learning perspectives (constructivism / behaviourism) in your way of learning.

Principal learning theories: practical examples

In this section we will introduce some examples of practical applications from the different learning theories:

| Learning theory | Example |

|---|---|

| Behaviorist | Dreyfuss model for skill acquisition. |

| Cognitivist | Human Memory and Learning from cognitive sciences |

| Constructivist | Bloom’s Taxonomy |

| Critical | The hidden curriculum |

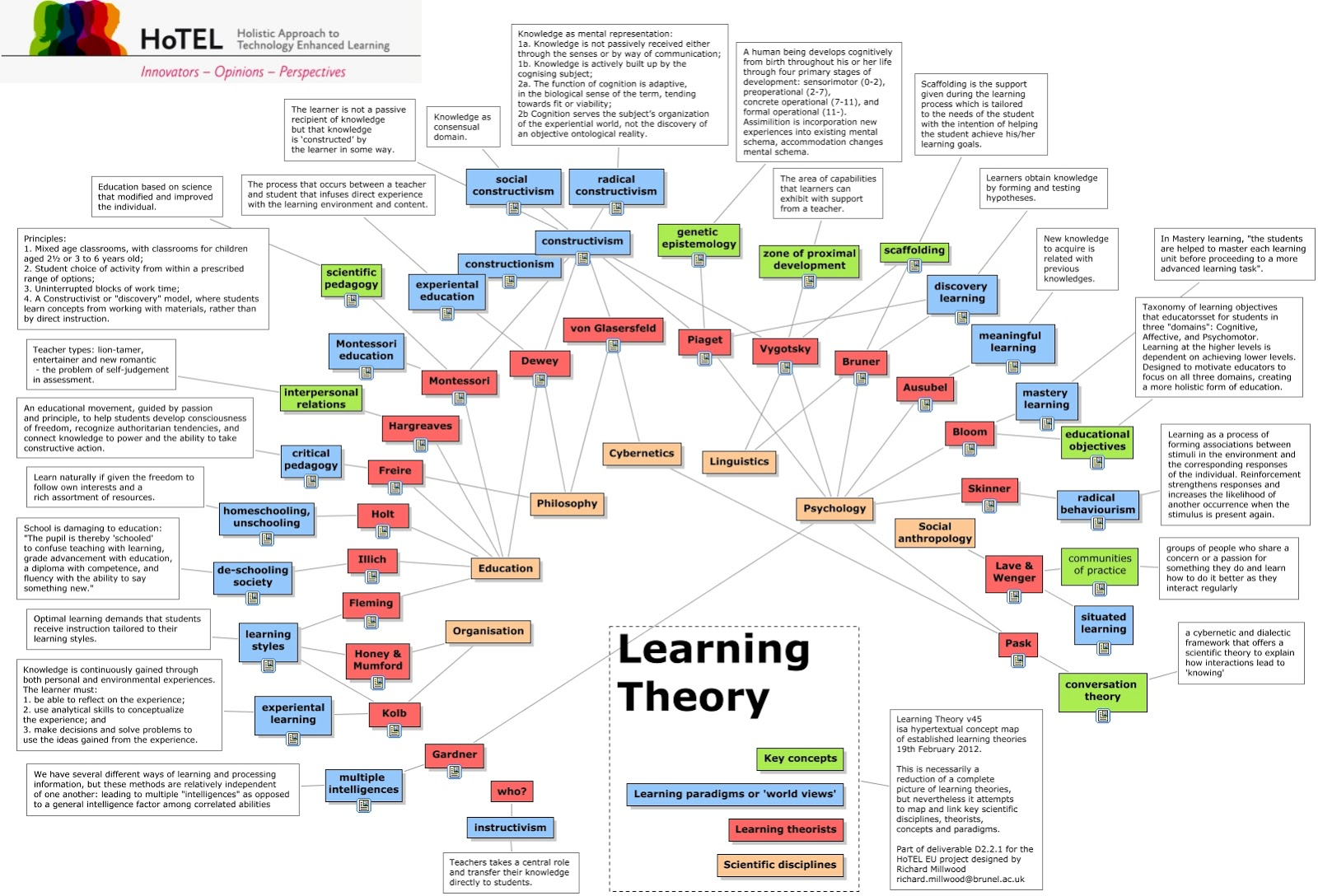

Behaviorist Learning theory: Dreyfuss model for skill acquisition

The Dreyfus model of skill acquisition presents a framework illustrating the process by which learners acquire skills through a combination of formal instruction and dedicated practice. It was presented by Hubert and Stuart Dreyfus in 1980 in a report on their research at the University of California, Berkeley, Operations Research Center for the United States Air Force Office of Scientific Research. Hubert Lederer Dreyfus (1929-2017) was a prominent American philosopher and a professor of philosophy. His areas of expertise encompassed phenomenology, existentialism, and the philosophy of psychology, literature, and artificial intelligence, exploring their profound philosophical implications. Stuart E. Dreyfus holds the position of professor emeritus in the Industrial Engineering and Operations Research Department at the University of California.

The Dreyfus model for skills acquisition by brothers Stuart and Huber Dreyfus uses a 5 stage from novice to expert.

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabThe stages follow a progression from rigid adherence (novice) to rules to an intuitive mode of reasoning based on tacit knowledge “silent knowledge” (expert).

The fundamental idea is that when teaching a concept, you have to tailor the style of teaching to where the learner is in their understanding and that progression follows a common pattern. Early stages of learning focus on concrete steps to imitate, the focus then shifts to understanding principles and finally into self-directed innovation.

The skill level is tied to a mental function transitioning from recollection (non-situational or situational), recognition (decomposed or holistic), decision (analytical or intuitive), and awareness (monitoring or absorbed)

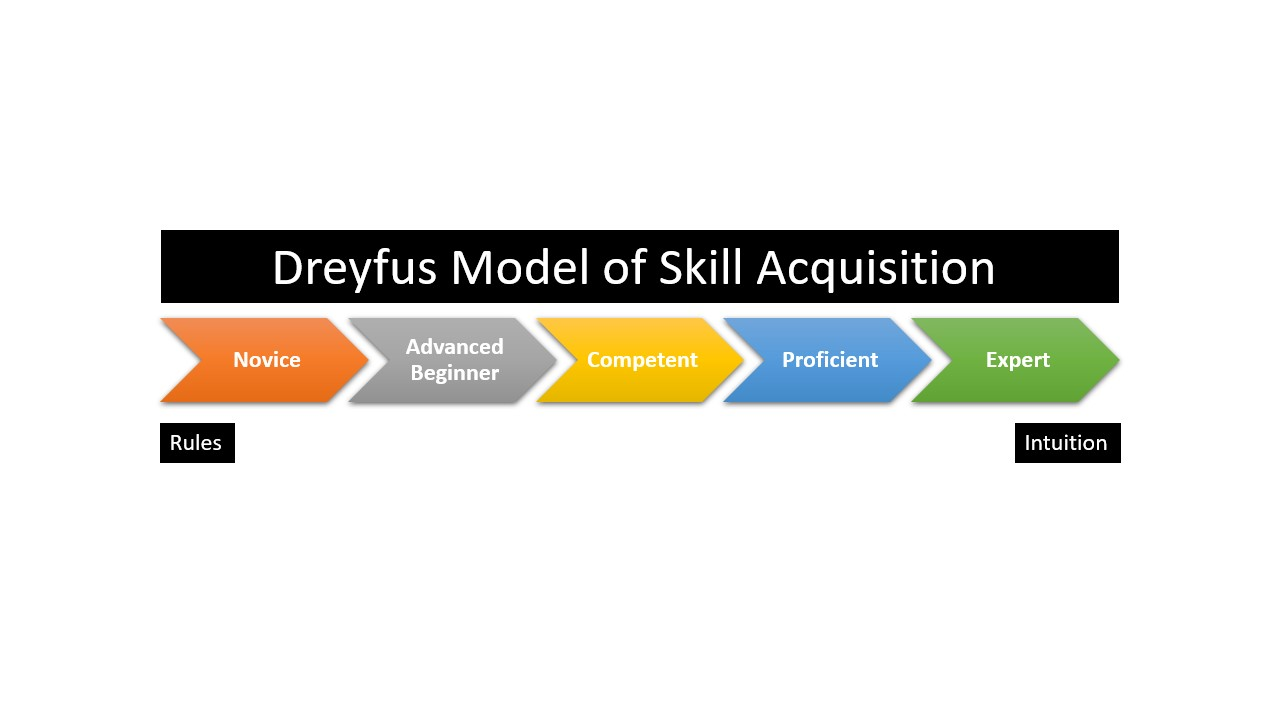

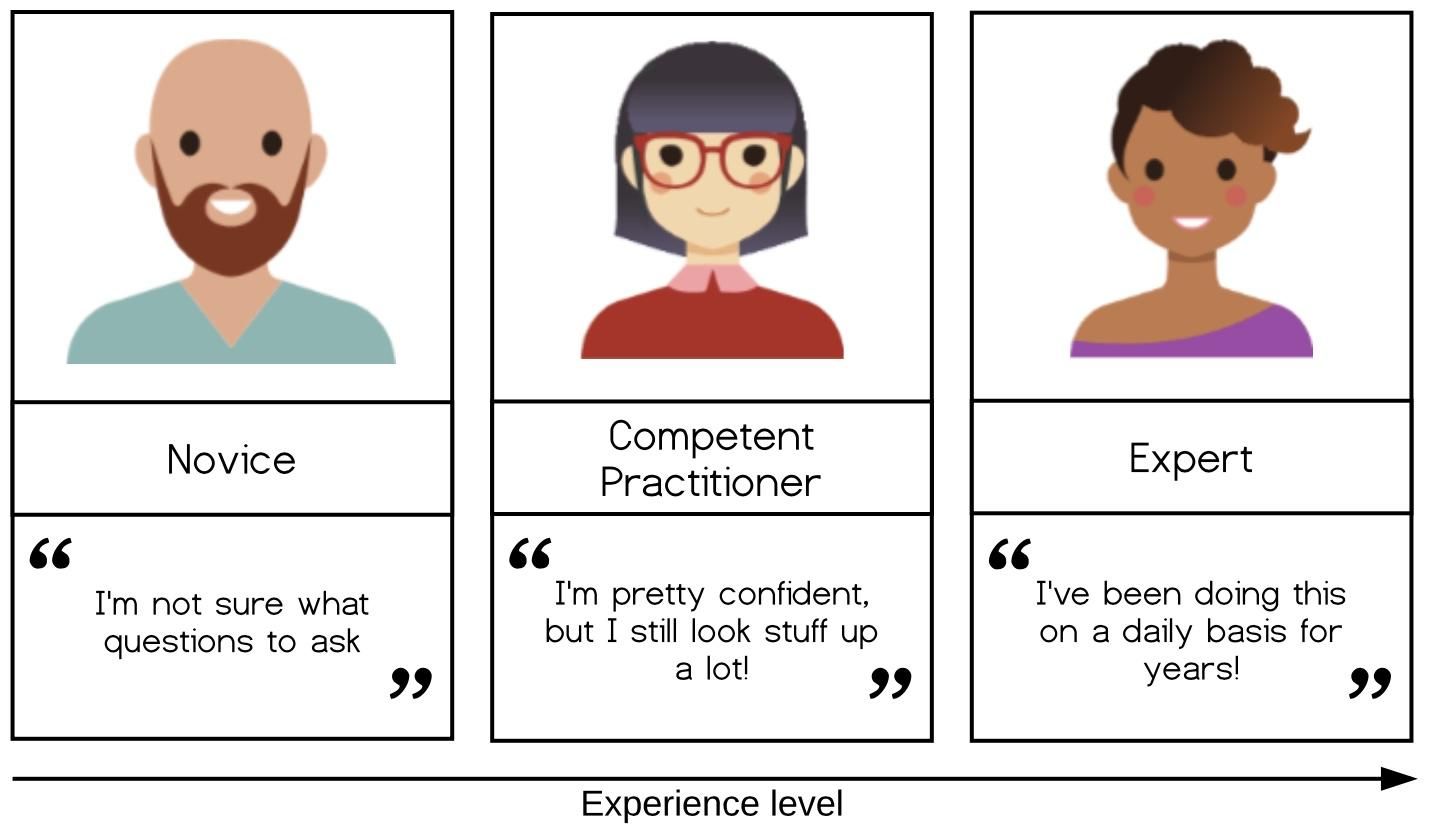

Example of Dreyfus model: the Carpentries

The Carpentries (a global organization building global capacity in essential data and computational skills for research) uses the Dreyfus model as its global approach for skill acquisition:

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tab-

Novice: someone who does not know what they do not know, i.e., they do not yet know what the key ideas in the domain are or how they relate. Novices may have difficulty formulating questions, or may ask questions that seem irrelevant or off-topic as they rely on prior knowledge, without knowing what is or is not related yet.

Example: A novice learner in a Carpentries workshop might never have heard of the bash shell, and therefore may have no understanding of how it relates to their file system or other programs on their computer.

-

Competent practitioner: someone who has enough understanding for everyday purposes. They will not know all the details of how something works and their understanding may not be entirely accurate, but it is sufficient for completing normal tasks with normal effort under normal circumstances.

Example: A competent practitioner in a Carpentries workshop might have used the shell before and understand how to move around directories and use individual programs, but they might not understand how they can fit these programs together to build scripts and automate large tasks.

-

Expert: someone who can easily handle situations that are out of the ordinary.

Example: An expert in a Carpentries workshop may have experience writing and running shell scripts and, when presented with a problem, immediately sees how these skills can be used to solve the problem.

The Carpentries was started by Greg Wilson and Brent Gorda and they coined the term “The Carpentries” for enabling researchers to do “computational thinking” and use tools of computation effectively.

The Style of the Carpentries are that teachers are where the learners are e.g. by doing live-coding together.

Cognitivist Learning Theory: Memory and learning

In a simple model from cognitive science, learning happens when information moves from working memory to long-term memory. This process can be impacted by environment

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabBased on Willingham 2009.

Read the following letter combination:

APH D BDN A CKG B DCI A- Hide them after 10 seconds

- Take a piece of paper and write what you remember

- Unhide them after 2 minutes

Check how many consecutive letters you can remember

Read the following letter combination

A PHD B DNA C KGB D CIA- Hide them after 10 seconds

- Take a piece of paper and write what you remember

- Unhide them after 2 minutes

- Check how many consecutive letters you can remember

The amount of space in working memory does not depend on the number of letters. It depends on the number of meaningful objects. In the 2nd round, the meaning of the words (long-term memory) or connecting words with a story helps to remember. It make room in working memory.

To facilitate learning, we as instructors have to make room in working memory.

What can we do to make room in working memory?

- Discuss one thing a teacher could do to avoid overloading their students’ working memory

- Write your proposal in the shared notes

What can we do to make room in working memory?

-

Chunking

Example: Short theoretical sessions alternated with practical sessions to allow the processing of the material

-

Avoid extraneous cognitive load

Example: Avoid too crowded slides

Cognitive load

There are 3 cognitive loads recognized by cognitive science:

- Intrinsic cognitive load: effort associated with a specific topic.

- Germane cognitive load: the (desirable) mental effort required to create linkages between new information and old.

- Extraneous cognitive load: everything else that distracts or gets in the way. It refers to the way information or tasks are presented to a learner.

Attention split effect

Split-attention occurs when learners are required to split their attention between at least two sources of information that have been separated either spatially or temporally

- Pick one task you teach in your lessons/courses

- Think and discuss within the room about the following questions

- What would be the extraneous load in performing this tak?

- How can you avoid it?

Six strategies for effective learning from cognitive psychology

Six strategies for effective learning (from “Understanding how we learn” Weinstein et al. 2018) are based on evidence from cognitive research.

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tab-

Spaced practice: Creating a study schedule that spreads study activities out over time

Spaced practice is the exact opposite of cramming. When you cram, you study for a long, intense period of time close to an exam. When you space your learning, you take that same amount of study time, and spread it out across a much longer period of time. Doing it this way, that same amount of study time will produce more long-lasting learning.

-

Interleaving: Switching between topics while studying

You shouldn’t study one idea, topic, or type of problem for too long. Instead, you should change it up often. Especially good for problem-solving topics like bioinformatics. Then you should jump from one topic to another and go back to the previous one, with the aim of developing the connections among topics.

-

Elaboration: Asking and explaining why and how things work

It can be used to mean a lot of different things. It involves explaining and describing ideas with many details. Elaboration also involves making connections among ideas you are trying to learn and connecting the material to your own experiences, memories, and day-to-day life.

-

Concrete examples: When studying / explaining abstract concepts, illustrating them with specific examples

The idea is to take an abstract concept and use real world examples to increase understanding and 2 examples are better than 1.

-

Dual coding: Combining worlds with visuals

Dual coding is combining words and visuals such as pictures, diagrams, graphic organizers, and so on. The idea is to provide two different representations of the information, both visual and verbal. Adding visuals to a verbal description can make the presented ideas more concrete, and provides two ways of understanding the presented ideas. The visuals should be meaningful.

-

Retrieval practice: Bringing learned information to mind from long term memory

Concept maps are examples of a retrieval practice when you bring out knowledge/memories from long-term memory

- Pick up one strategy per group

- Discuss about the strategy

- Did you understand it the same way?

- Do you have any questions?

- Find out an example on how you would implement it as a teacher/instructor (what would you do as a teacher in order to facilitate learning based on the strategy at hand)

We highly recommend to look at the materials in a book and a website and blog as they are intended to teach about principles of learning and to provide teachers and students with flexible guiding principles to guide learning and studying. In “Training techniques to enhance learner participation and engagement” tutorial, a number of teaching practices are described. You should try to reconnect them to these learning strategies, i.e. try to understand how the proposed teaching practices facilitate learning based on these six strategies.

Seven learning principles from cognitive sciences

From “How Learning works” Ambrose et al. 2010

-

Principle P1: Students’ prior knowledge can help or hinder learning.

Hindrances include prior knowledge which may be accurate but insufficient to support learning new material. Inappropriate for the specific class, thus distorting comprehension of new material; or, completely inaccurate.

-

Principle P2: How students organise knowledge influences how they learn and apply what they know.

Generally, people organize knowledge “as a function of their experience, the nature of their knowledge, and the role that that knowledge plays in their lives”

-

Principle P3: Students motivation determines, directs and sustains what they do learn.

Ambrose et al. 2010 define motivation as “the personal investment that an individual has in reaching a desired state or outcome” and identify three core concepts for understanding motivation

- the subjective value of a goal

- the expectancies for successfully reaching the goal

- ??

-

Principle P4: To develop mastery, students must acquire component skills, practice integrating them, and know when to apply what they have learned

Mastery refers to “the attainment of a high degree of competence with a particular area”. It could be either beneficial or detrimental.

-

Principle P5: Goal-directed practice coupled with targeted feedback enhances the quality of students’ learning

Learning and performance are advanced when students employ a methodology that

- focuses on a specific performance goal

- pinpoints a suitable level of challenge relative to students’ current performance,

- is in an amount and frequency sufficient to meet the performance criteria.

-

Principle P6: Students’ current level of development interacts with the social, emotional, and intellectual climate of the course to impact learning

Ambrose et al. 2010 maintain that “student-centered teaching requires us to teach students, not content”.

-

Principle P7: To become self-directed learners, students must learn to monitor and adjust their approaches to learning.

This principle relates to metacognition, or “the process of reflecting on and directing one’s own thinking”. You can find more information on the connection of metacognition to student learning and performance here Stanton et al. 2021.

Students develop metacognitive skills by learning to

- assess the task at hand,

- evaluate their own strengths and weaknesses,

- plan appropriate approaches to complete the task,

- apply strategies to monitor their performance, while making adjustments to the selected approach.

There is a great deal of literature on how learning works.

The reason why we mention these three books is that they show how to integrate effective, research based strategies for learning into classroom practice.

Educational practice usually does not rely on research findings. People tend to rely on their intuitions about what’s best for learning. But relying on intuition may be a bad idea for teachers and learners alike.

“How Learning Works” (Ambrose et al. 2010)

This book presents a set of evidence-based principles for how to help people learn that is grounded in cognitive theory (that is, the science of instruction). It tries to help teachers understand how research in the science of learning can improve their reaching.

The book is organised around seven learning principles. Each principle is based on research evidence from the science of learning and the science of instruction.

Cognitive psychologists, neuroscientists, and biologists all have produced a revealing body of research over the past several decades on how human beings learn, but often translating these findings into the classroom is overwhelming for busy instructors.

“Small Teaching” bridges the gap between research and practice by providing a fully developed strategy for making deliberate, structured, and incremental steps towards tuning into how students are hardwired to learn.

The book introduces small activities that require minimal preparation and grading. The models presented are specifically designed to be used as both one-time experiences to innovate a course session or unit plan as well as a menu of options that can be combined into an entirely new teaching approach.

“Understanding how we learn” Weinstein et al. 2018

By the “learning scientists” Weinstein and Sumeracki (and illustrated by Oliver Caviglioli), the books examines the cognitive psychology’s application to education

It is designed to convey the concepts of research to the reality of an instructor’s classroom. The book proposes 6 strategies for effective learning (based on evidence from cognitive research). It is structured in four parts:

- Evidence-based education and the science of learning

- Basics of human cognitive processes

- Strategies for effective learning

- Tips for students, teachers, and parents

The Carpentries Instructor Training materials

The Carpentries is a community of volunteers teaching computational and data management skills worldwide. The community also developed training materials to teach pedagogical skills. Much of the GTN TtT was inspired by the pedagogical materials from the Carpentries and the ELIXIR TtT.

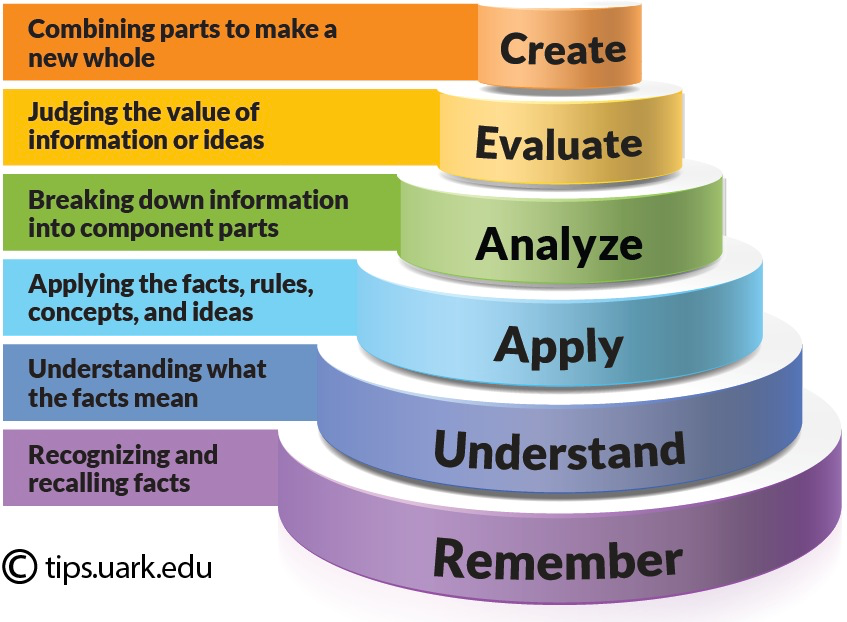

Constructivist Learning Theory: The Bloom’s Taxonomy

And one of the most used “models” or concepts is the one based on the Bloom’s six categories of cognitive skills. This tool is important to develop training, but not only.

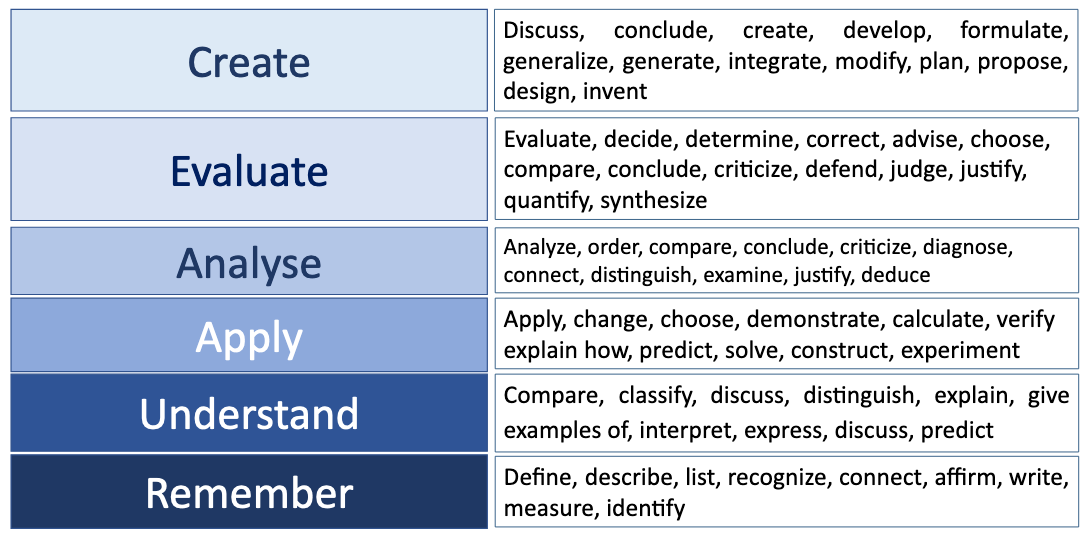

Bloom’s taxonomy is a set of six categories of cognitive skills, that are accompanied by actionable verb.

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabFrom bottom to top:

- Remembering (original Knowledge): involves recognizing or remembering facts, terms, basic concepts, or answers without necessarily understanding what they mean.

- Understand (original comprehension): involves demonstrating an understanding of facts and ideas by organizing, summarizing, translating, generalizing, giving descriptions, and stating the main ideas.

- Apply/Application: involves using acquired knowledge—solving problems in new situations by applying acquired knowledge, facts, techniques and rules. Learners should be able to use prior knowledge to solve problems, identify connections and relationships and how they apply in new situations.

- Analyze: involves examining and breaking information into component parts, determining how the parts relate to one another, identifying motives or causes, making inferences, and finding evidence to support generalizations.

- Evaluate: involves presenting and defending opinions by making judgments about information, the validity of ideas, or quality of work based on a set of criteria

- Create (original synthesize):involves building a structure or pattern from diverse elements; it also refers to the act of putting parts together to form a whole.

It is important to highlight that, under this framework, critical thinking is considered a combination of analyzing, evaluating and creating, i.e. the top three layers of the taxonomy. Blooms taxonomy levels are very useful to align instruction with learners’ level of complexity of thinking as well as experience.

What are the uses of this tool?

- For learners

- Help to structure their knowledge

- For instructors

- Knowing at which level of cognitive complexity you want to teach

-

Write Learning Outcomes

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabFigure 8: ACTION verbs express levels of cognitive complexity - Design instruction and learning experiences i.e. how you are to teach/train, which infrastructure and how to present the materials etc

- Assess learning (taking place during curricula or course and after)

- Align instruction with learners’ level of complexity of thinking as well as experience.

Critical Learning Theory: The Hidden Curriculum Theory

The concept of hidden curriculum refers to the learning that is incorporated by students though these aspects do not appear explicitly in the official curriculum, relying on the organisational aspects of classroom life that are generally not perceived by either students or teachers (Giroux 2004).

According the Hidden Curriculum Theory, what students learn from the formally sanctioned content of the curriculum is much less important than what they learn from the ideological assumptions embodied in the communicative systems. Through the hidden curriculum, students would internalise values that emphasise respect for authority, punctuality, cleanliness, docility and conformity (Giroux 2004). It considers that elements such as exposure to a core of common subjects would lead to a dissolution of individuality in the mass, in the collective, to a standardisation and homogenisation of psychologies (Olivo 2005).

According the Hidden Curriculum Theory, if there is really an interest in fostering critical thinking, the discursive mode that should dominate in the classroom should be the interrogative one. It considers that questioning is a way of thinking, and that is why thinking is not only deriving conclusions, but often consists of the opposite: starting from the accepted conclusions of a community and turning them upside down (Sztajnszrajber 2013).

According this theory, technological tools, due to their design, do not act just as neutral means for transmitting information, but they also transmit values and habits of thought (Anders 1980). As Giroux 2004 notes, no matter how progressive an approach to critical thinking may be, it will squander its own potential if it operates on the basis of a web of social relations in the classroom that are authoritarianly hierarchical and promote passivity, docility and silence.

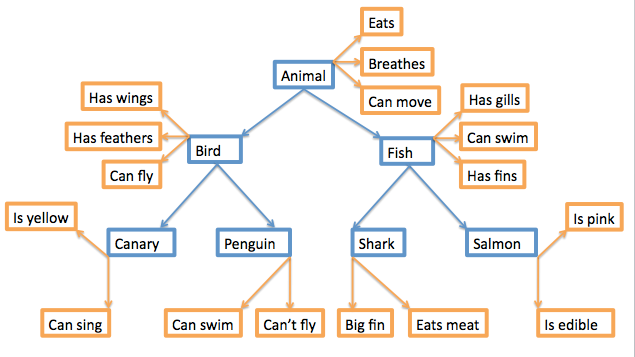

Mental models

Mental model is a collection of concepts and facts, along with the relationships between those concepts, that a person has about a topic or field. It is how people organize their knowledge

You can think of mental models as a graph with nodes (facts, concepts) and edges (connections), as seen in the figure of the mental model of animals below:

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabThe mental model of an expert in any given subject will be far larger and more complex than that of a novice, including both more concepts and more detailed and numerous relationships. Linking with Dreyfus model:

- A novice has a minimal mental model of surface features of the domain. Inaccuracies based on limited prior knowledge may interfere with adding new information. Predictions are likely to borrow heavily from mental models of other domains which seem superficially similar.

- A competent practitioner has a mental model that is useful for everyday purposes. Most new information they are likely to encounter will fit well with their existing model. Even though many potential elements of their mental model may still be missing or wrong, predictions about their area of work are usually accurate.

- An expert has a densely populated and connected mental model that is especially good for problem solving. They quickly connect concepts that others may not see as being related. They may have difficulty explaining how they are thinking in ways that do not rely on other features unique to their own mental model.

Misconceptions

- Simple factual errors: These are the easiest to correct.

- Broken models: We can address these by having learners reason through examples to see contradictions.

- Fundamental beliefs: These beliefs are deeply connected to the learner’s social identity and are the hardest to change.

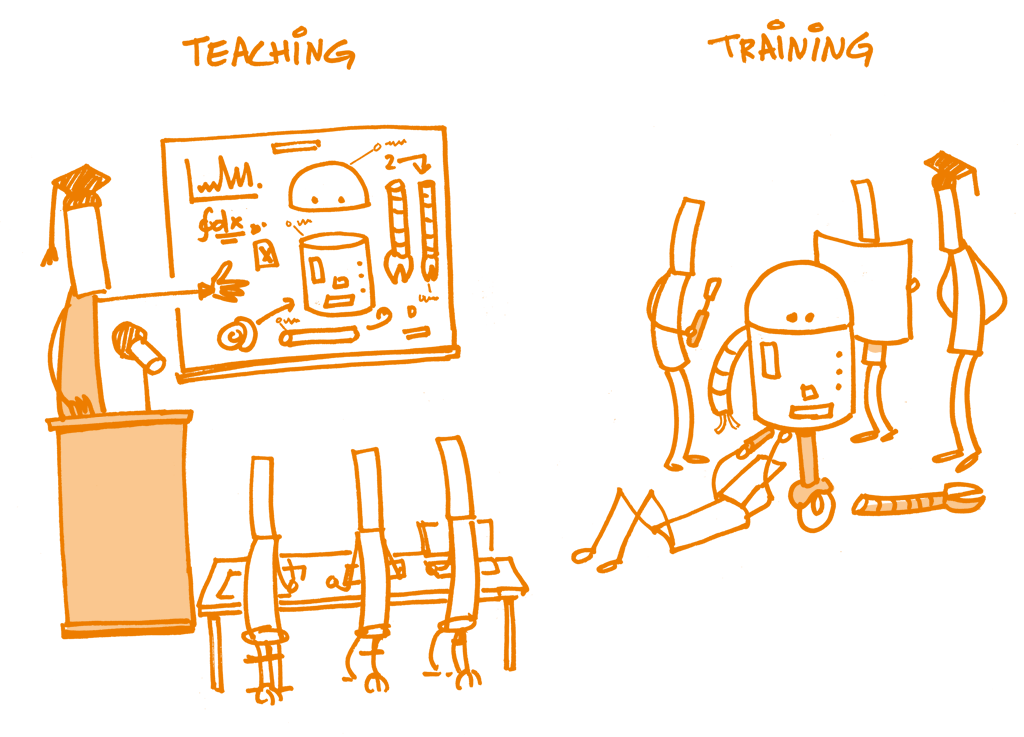

Teaching or training?

- Based on your experience, what are the differences between teaching and training?

- Write your reflexions in the shared notes

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabTeaching is more theoretical and abstract, while training (when done well) is more hands-on and practical.

Teaching seeks to impart knowledge and provide information, while training is intended to develop abilities.

- Teach: to provide knowledge, instruction or information

- Train: to develop abilities through practice with instruction or supervision

For example, it is possible to teach someone about buoyancy, fluid dynamics, water displacement and coastline safety, but that knowledge will not make them a good swimmer. Specific, practical and applied training is necessary to use abstract knowledge to learn or master a skill. In many cases, teaching and training are complementary. Vocational training programs often combine teaching and training quite nicely.

Conclusion

After going through the theory of learning with the 6 strategies and the Ambrose 7 principles as well as the differences between teaching and training, the next step is to understand how these elements can be applied in designing an effective curriculum developmental trajectory.