Python - Type annotations

| Author(s) |

|

| Editor(s) |

|

| Reviewers |

|

OverviewQuestions:

Objectives:

What is typing?

How does it improve code?

Can it help me?

Requirements:

Understand the utility of annotating types on one’s code

Understand the limits of type annotations in python

Time estimation: 30 minutesLevel: Intermediate IntermediateSupporting Materials:Published: Oct 19, 2022Last modification: Feb 13, 2023License: Tutorial Content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The GTN Framework is licensed under MITpurl PURL: https://gxy.io/GTN:T00100version Revision: 2

Best viewed in a Jupyter NotebookThis tutorial is best viewed in a Jupyter notebook! You can load this notebook one of the following ways

Run on the GTN with JupyterLite (in-browser computations)

Launching the notebook in Jupyter in Galaxy

- Instructions to Launch JupyterLab

- Open a Terminal in JupyterLab with File -> New -> Terminal

- Run

wget https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/data-science/tutorials/python-typing/data-science-python-typing.ipynb- Select the notebook that appears in the list of files on the left.

Downloading the notebook

- Right click one of these links: Jupyter Notebook (With Solutions), Jupyter Notebook (Without Solutions)

- Save Link As..

In some languages type annotations are a core part of the language and types are checked at compile time, to ensure your code can never use the incorrect type of object. Python, and a few other dynamic languages, instead use “Duck Typing” wherein the type of the object is less important than whether or not the correct methods or attributes are available.

However, we can provide type hints as we write python which will allow our editor to type check code as we go, even if it is not typically enforced at any point.

AgendaIn this tutorial, we will cover:

Types

Types used for annotations can be any of the base types:

str

int

float

bool

None

...

or they can be relabeling of existing types, letting you create new types as needed to represent your internal data structures

from typing import NewType

NameType = NewType("NameType", str)

Point2D = NewType("Point2D", tuple[float, float])

You might be on a python earlier than 3.9. Please update, or rewrite these as Tuple and List which must be imported.

But why?

Imagine for a minute you have a situation like the following, take a minute to read and understand the code:

# Fetch the user and history list

(history_id, user_id) = GetUserAndCurrentHistory("hexylena")

# And make sure all of the permissions are correct

history = History.fetch(history_id)

history.share_with(user_id)

history.save()

Question

- Can you be sure the

history_idanduser_idare in the correct order? It seems like potentially not, given the ordering of “user” and “history” in the function name, but without inspecting the definition of that function we won’t know.- What happens if

history_idanduser_idare swapped?

- This is unanswerable without the code.

Depending on the magnitude of

history_idanduser_id, those may be within allowable ranges. Take for example

User History Id 1 1 1 2 2 3 2 4 Given

user_id=1andhistory_id=2we may intend that the second row in our tables, history #2 owned by user #1, is shared with that user, as they’re the owner. But if those are backwards, we’ll get a situation where history #1 is actually associated with user #1, but instead we’re sharing with user #2. We’ve created a situation where we’ve accidentally shared the wrong history with the wrong user! This could be a GDPR violation for our system and cause a lot of trouble.

However, if we have type definitions for the UserId and HistoryId that declare them as their own types:

from typing import NewType

UserId = NewType("UserId", int)

HistoryId = NewType("HistoryId", int)

And then defined on our function, e.g.

def GetUserAndCurrentHistory(username: str) -> tuple[UserId, HistoryId]:

x = UserId(1) # Pretend this is fetching from the database

y = HistoryId(2) # Likewise

return (x, y)

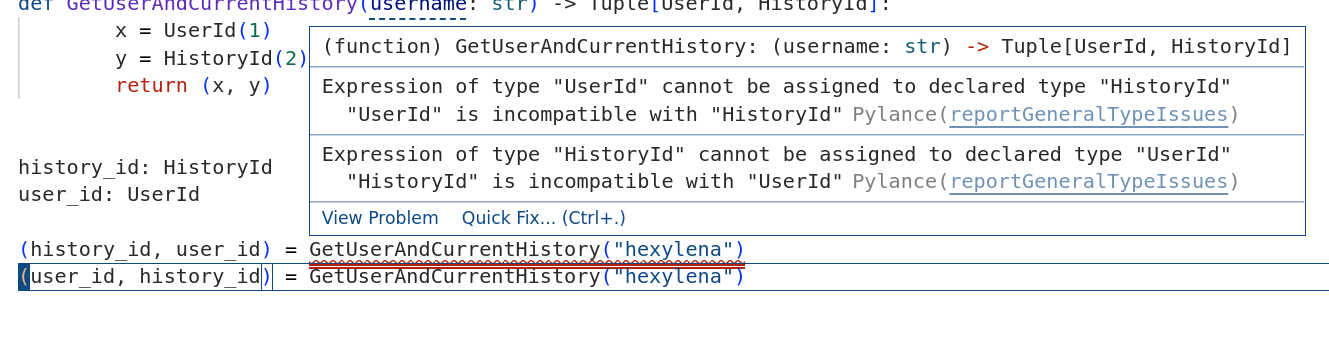

we would be able to catch that, even if we call the variable user_id, it will still be typed checked.

history_id: HistoryId

user_id: UserId

(user_id, history_id) = GetUserAndCurrentHistory("hexylena")

(history_id, user_id) = GetUserAndCurrentHistory("hexylena")

If we’re using a code editor with typing hints, e.g. VSCode with PyLance, we’ll see something like:

Here we see that we’re not allowed to call this function this way, it’s simply impossible.

QuestionWhat happens if you execute this code?

It executes happily. Types are not enforced at runtime. So this case where they’re both custom types around an integer, Python sees that it expects an int in both versions of the function call, and that works fine for it. That is why we are repeatedly calling them “type hints”, they’re hints to your editor to show suggestions and help catch bugs, but they’re not enforced. If you modified the line

y = HistoryId(2)to be something likey = "test", the code will also execute fine. Python doesn’t care that there’s suddenly a string where you promised and asked for, an int. It simply does not matter.However, types are checked when you do operations involving them. Trying to get the

len()of an integer? That will raise anTypeError, as integers don’t support thelen()call.

Typing Variables

Adding types to variables is easy, you’ve seen a few examples already:

a: str = "Hello"

b: int = 3

c: float = 3.14159

d: bool = True

Complex Types

But you can go further than this with things like tuple and list types:

e: list[int] = [1, 2, 3]

f: tuple[int, str] = (3, "Hi.")

g: list[tuple[int, int]] = [(1, 2), (3, 4)]

Typing Functions

Likewise you’ve seen an example of adding type hints to a function:

def reverse_list_of_ints(a: list[int]) -> list[int]:

return a[::-1]

But this is a very specific function, right? We can reverse lists with more than just integers. For this, you can use Any:

from typing import Any

def reverse_list(a: list[Any]) -> list[Any]:

return a[::-1]

But this will lose the type information from the start of the function to the end. You said it was a list[Any] so your editor might not provide any type hints there, even though you could know, that calling it with a list[int] would always return the same type. Instead you can do

from typing import TypeVar

T = TypeVar("T") # Implicitly any

def reverse_list(a: list[T]) -> list[T]:

return a[::-1]

Now this will allow the function to accept a list of any type of value, int, float, etc. But it will also accept types you might not have intended:

w: list[tuple[int, int]] = [(1, 2), (3, 4), (5, 8)]

reverse_list(w)

We can lock down what types we’ll accept by using a Union instead of Any. With a Union, we can define that a type in that position might be any one of a few more specific types. Say your function can only accept strings, integers, or floats:

from typing import Union

def reverse_list(a: list[Union[int, float, str]]) -> list[Union[int, float, str]]:

return a[::-1]

Here we have used a Union[A, B, ...] to declare that it can only be one of these three types.

Question

Are both of these valid definitions?`

q1: list[Union[int, float, str]] = [1, 2, 3] q2: list[Union[int, float, str]] = [1, 2.3214, "asdf"]If that wasn’t what you expected, how would you define it so that it would be?

Yes, both are valid, but maybe you expected a homogeneous list. If you wanted that, you could instead do

q3: Union[list[int], list[float], list[str]] = [1, 2, 3] q4: Union[list[int], list[float], list[str]] = [1, 2.3243, "asdf"] # Fails

Optional

Sometimes you have an argument to a function that is truly optional, maybe you have a different code path if it isn’t there, or you simply process things differently but still correctly. You can explicitly declare this by defining it as Optional

from typing import Optional

def pretty(lines: list[str], padding: Optional[str] = None) -> None:

for line in lines:

if padding:

print(f"{padding} {line}")

else:

print(line)

lines = ["hello", "world", "你好", "世界"]

# Without the optional argument

pretty(lines)

# And with the optional

pretty(lines, "★")

While this superficially looks like a keyword argument with a default value, however it’s subtly different. Here an explicit value of None is allowed, and we still know that it will either be a string, or it will be None. Not something that was possible with just a keyword argument.

Testing for Types

You can use mypy to ensure that these type annotations are working in a project, this is a step you could add to your automated testing, if you have that. Using the HistoryId/UserId example from above, we can write that out into a script and test it out by running mypy on that file:

$ mypy tmp.py

tmp.py:15: error: Incompatible types in assignment (expression has type "UserId", variable has type "HistoryId")

tmp.py:15: error: Incompatible types in assignment (expression has type "HistoryId", variable has type "UserId")

Here it reports the errors in the console, and you can use this to prevent bad code from being committed.

Exercise

Here is an example module that would be stored in corp/__init__.py

def repeat(x, n):

"""Return a list containing n references to x."""

return [x]*n

def print_capitalized(x):

"""Print x capitalized, and return x."""

print(x.capitalize())

return x

def concatenate(x, y) :

"""Add two strings together."""

return x + y

And here are some example invocations of that module, as found in test.py

from corp import *

x = repeat("A", 3) # Should return ["A", "A", "A"]

y = print_capitalized("hElLo WorLd") # Should print Hello World

z = concatenate("Hi", "Bob") # HiBob

Hands On: Add type annotations

- Add type annotations to each of those functions AND the variables

x,y,z- How did you know which types were appropriate?

- Does

mypyapprove of your annotations? (Runmypy test.py, once you’ve written the above files out to their appropriate locations.)

The proper annotations:

def repeat(x: str, n: int) -> list[str]: # Or from typing import TypeVar T = TypeVar("T") def repeat(x: T, n: int) -> list[T]: def print_capitalized(x: str) -> str: def concatenate(x: str, y:str) -> str:and

x: list[str] = ... y: str = ... z: str = ...- You might have discovered this by a combination of looking at the function definitions and their documentation, and perhaps also the sample invocations and what types were passed there.

- We hope so!

Automation with MonkeyType

You can use MonkeyType to automatically apply type annotations to your code. Based on the execution of the code, it will make a best guess about what types are supported.

Hands On: Using MonkeyType to generate automatic annotations

- Create a folder for a module named

some- Touch

some/__init__.pyto ensure it’s importable as a python moduleCreate

some/module.pyand add the following contents:def add(a, b): return a + BCreate a script that uses that module:

from some.module import add add(1, 2)pip install monkeytypeRun MonkeyType to generate the annotations

monkeytype run myscript.pyView the generated annotations

monkeytype stub myscript.py

Question

- What was the output of that command?

- This function will accept strings as well, add a statement to exercise that in

myscript.pyand re-runmonkeytype runandmonkeytype stub. What is the new output?

The expected output is:

def add(a: int, b: int) -> int: ...You can add a statement like

add("a", "b")belowadd(1, 2)to see:def add(a: Union[int, str], b: Union[int, str]) -> Union[int, str]: ...

QuestionWhy is it different?

Because MonkeyType works by running the code provided (

myscript.py) and annotating based on what executions it saw. In the first invocation it had not seen any calls toadd()with strings, so it only reportedintas acceptable types. However, the second time it sawstrs as well. Can you think of another type that would be supported by this operation, that was not caught? (list!)

Question

- Does that type annotation make sense based on what you’ve learned today?

- Can you write a better type annoation based on what you know?

- It works, but it’s not a great type annotation. Here the description looks like it can accept two

ints and return astrwhich isn’t correct.Here is a better type annotation

from typing import TypeVar T = TypeVar("T", int, str, list) def add(a: T, b: T) -> T: return a + b