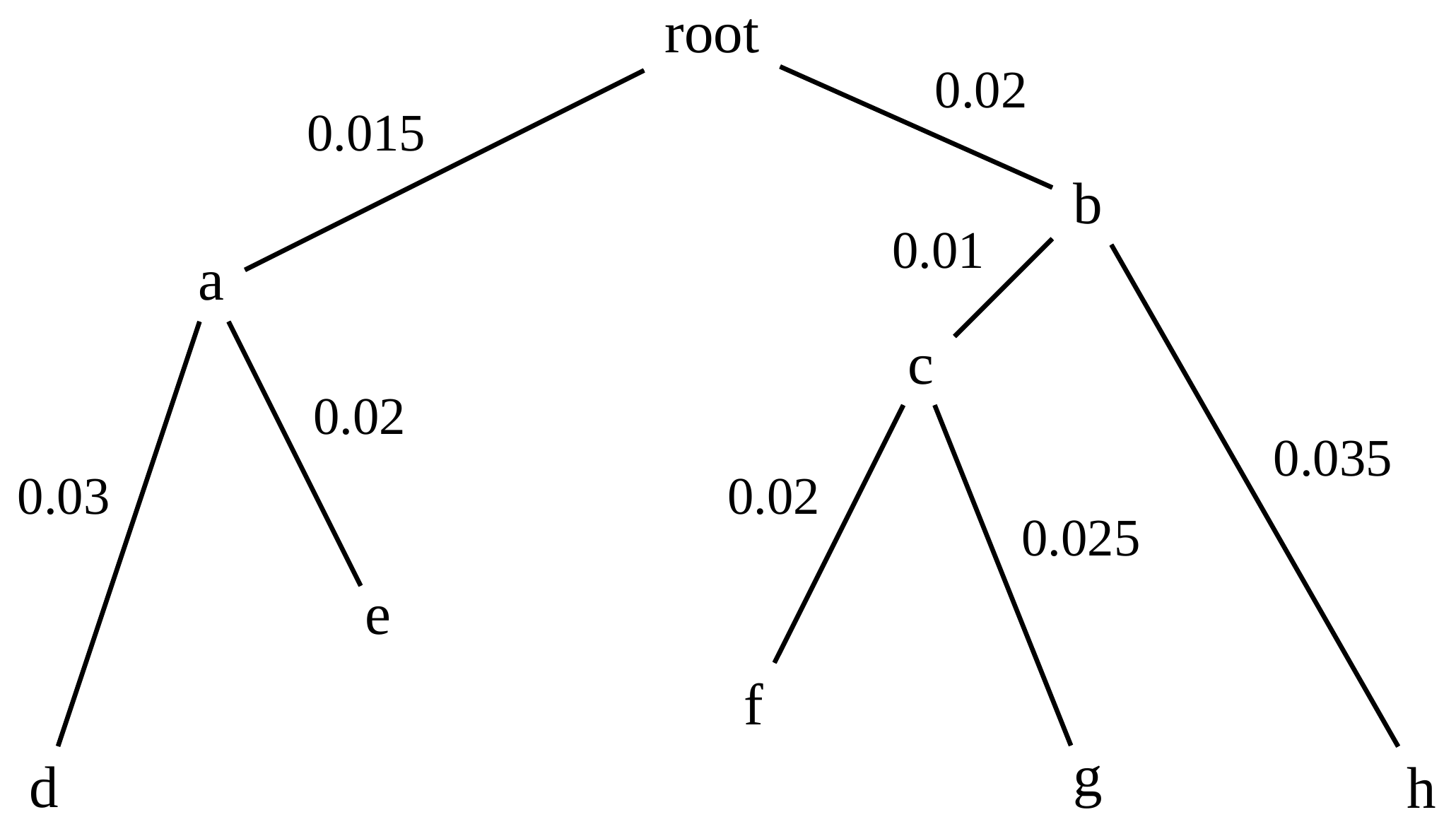

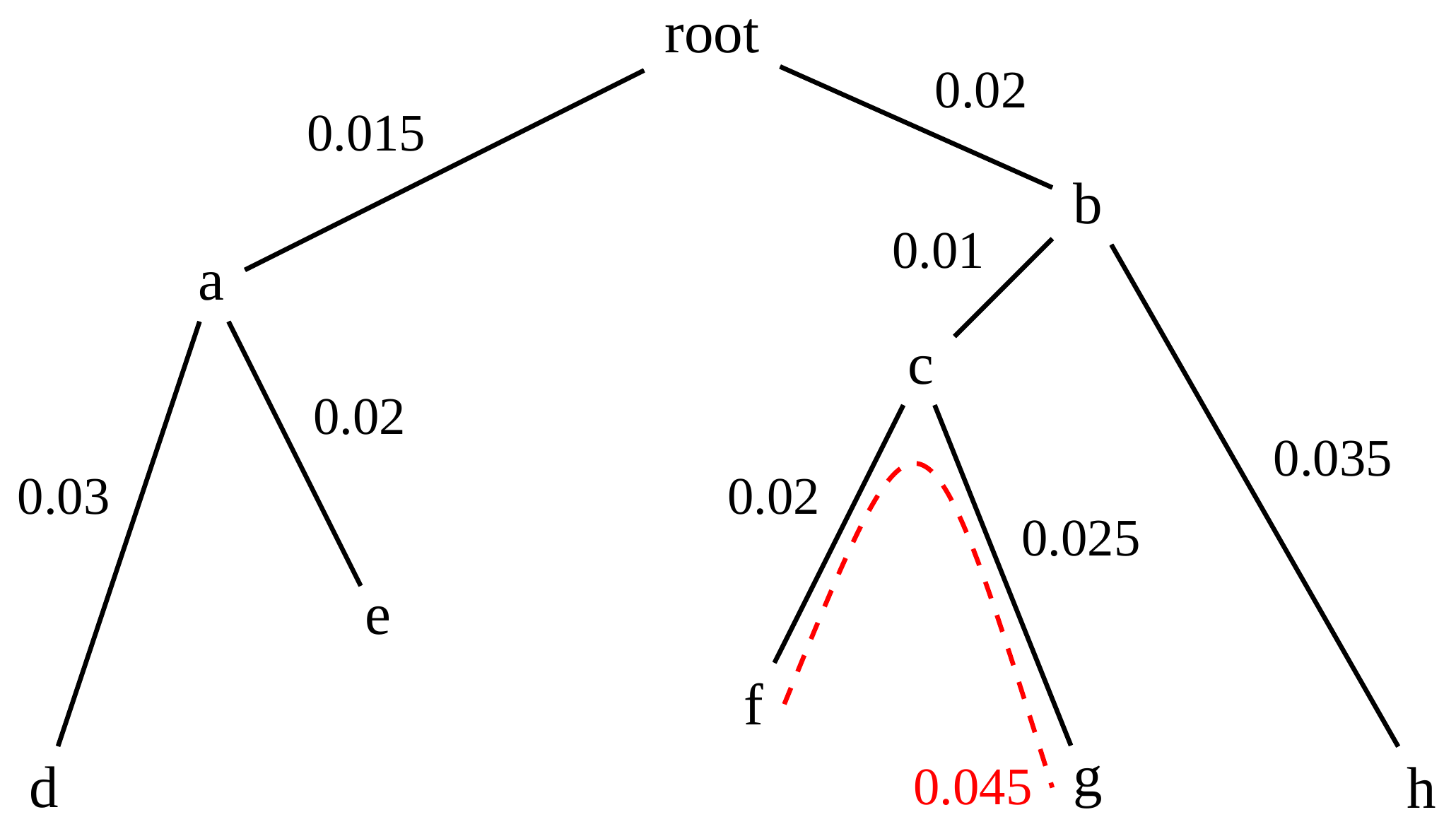

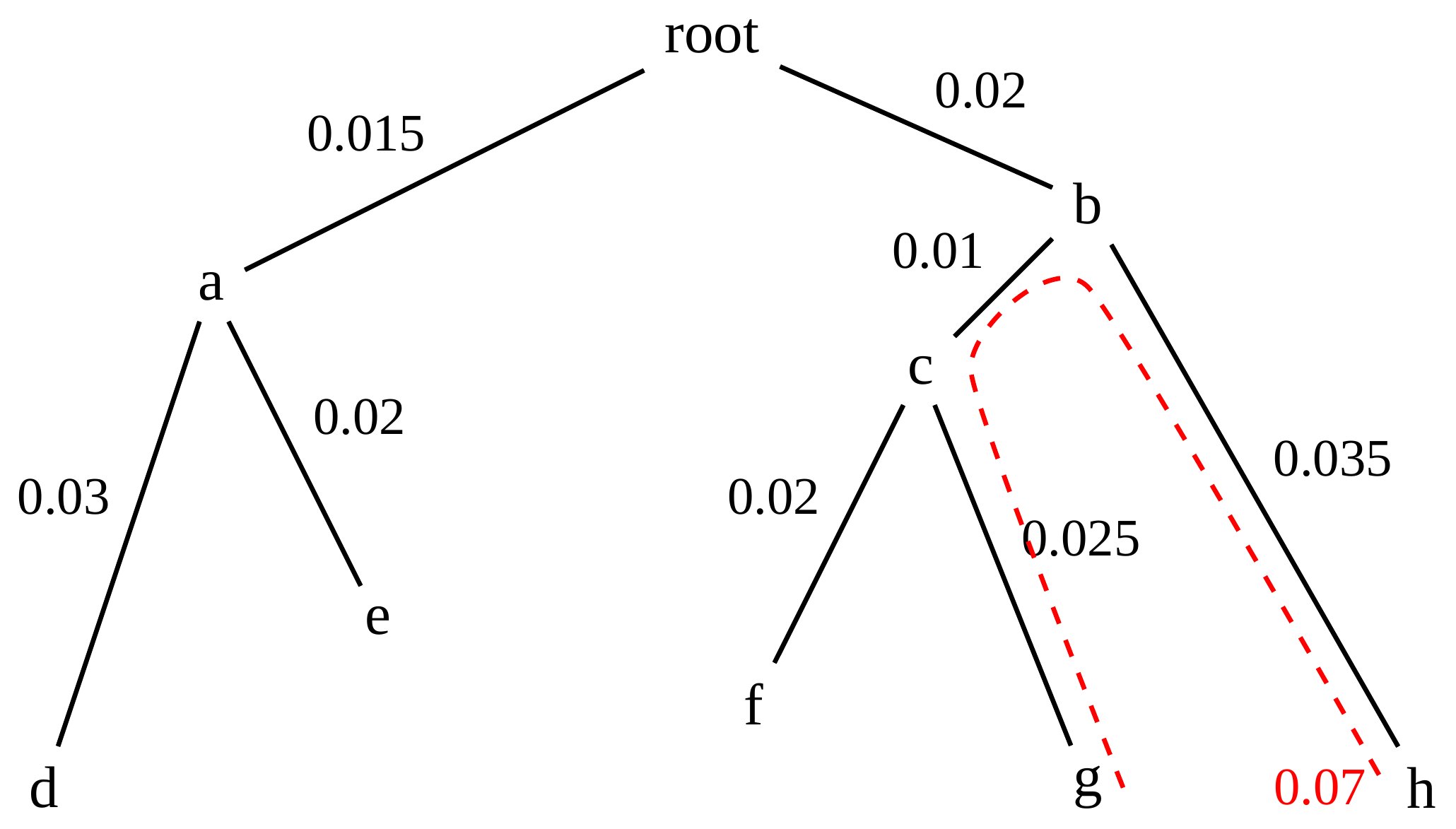

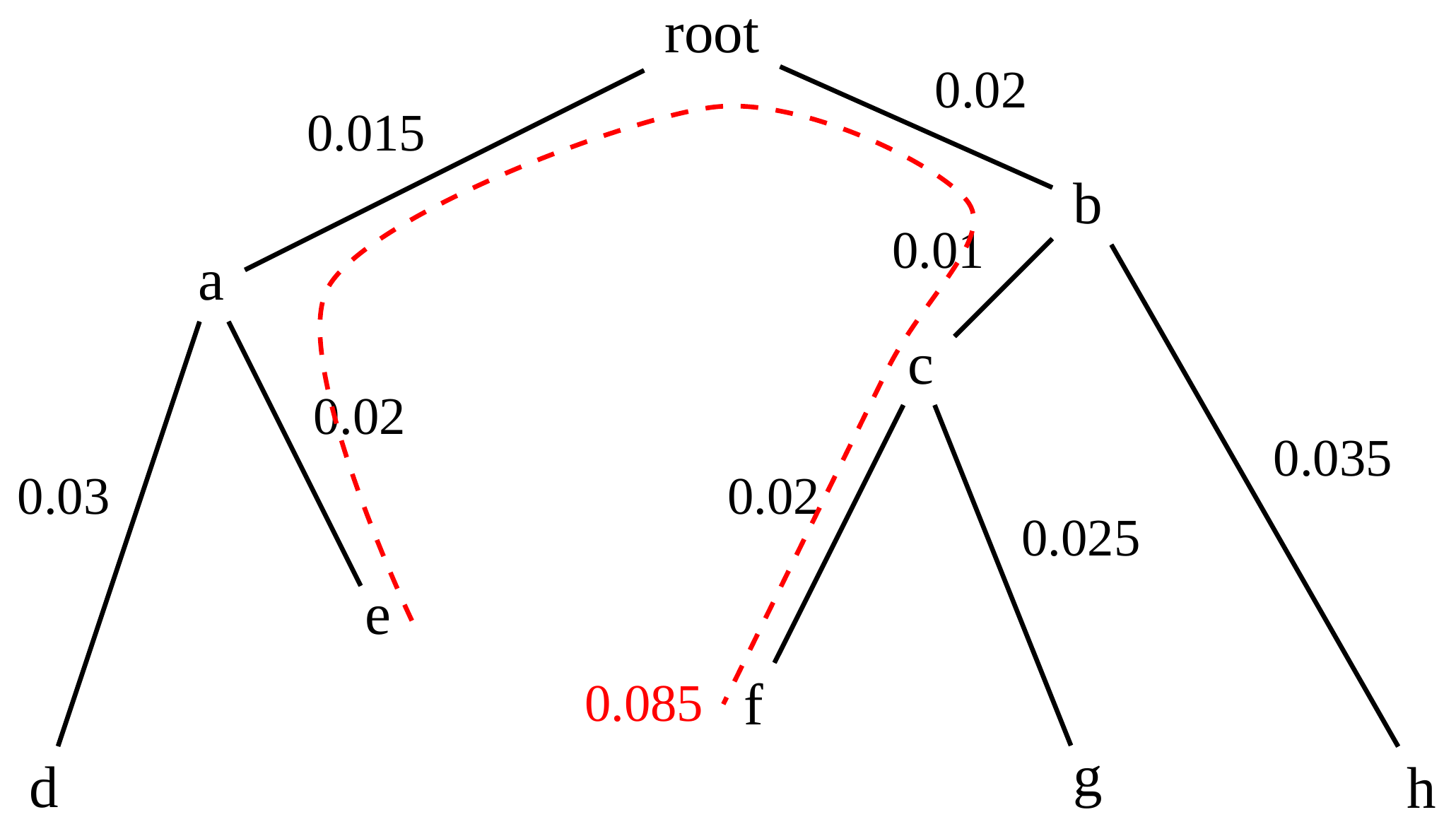

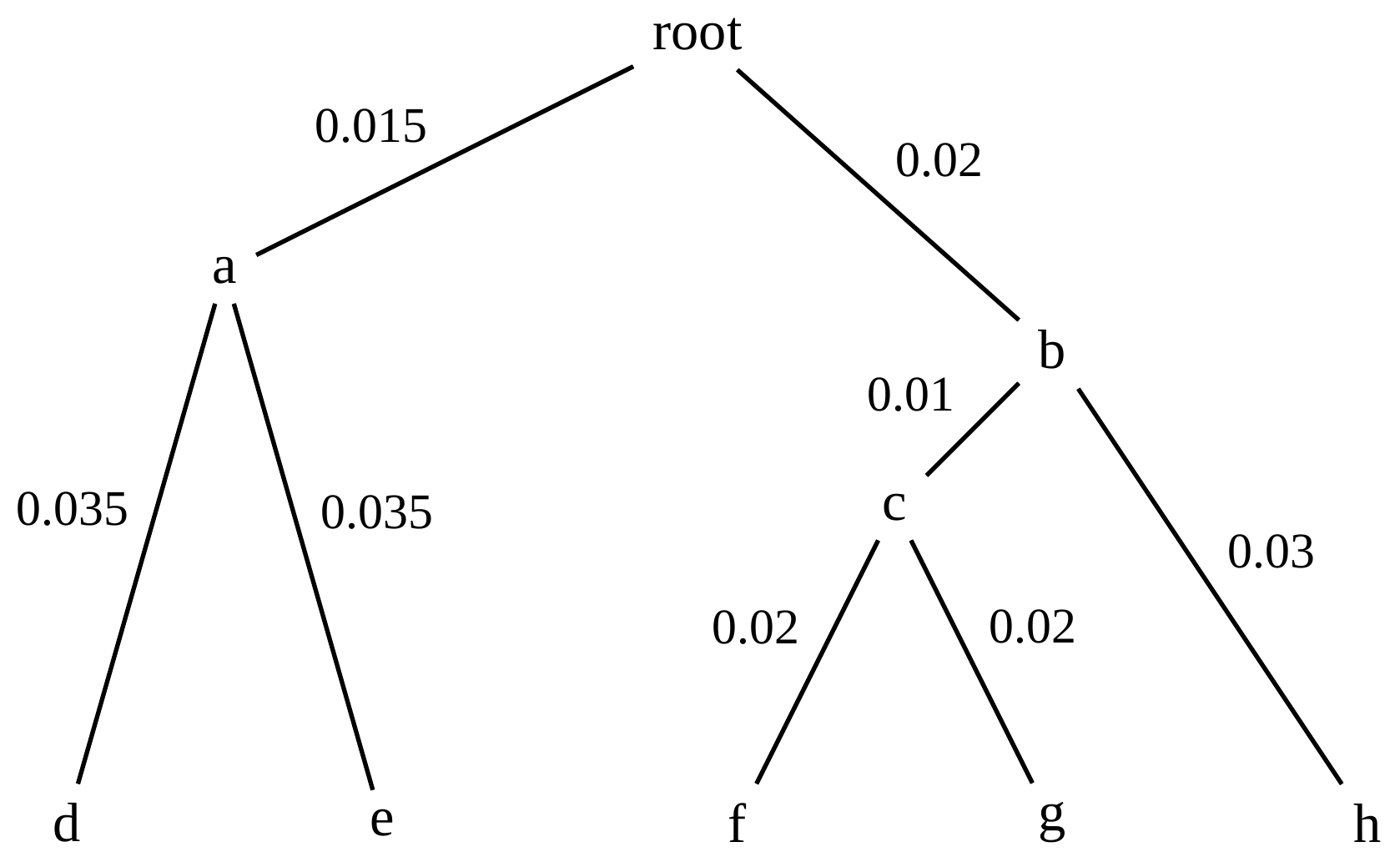

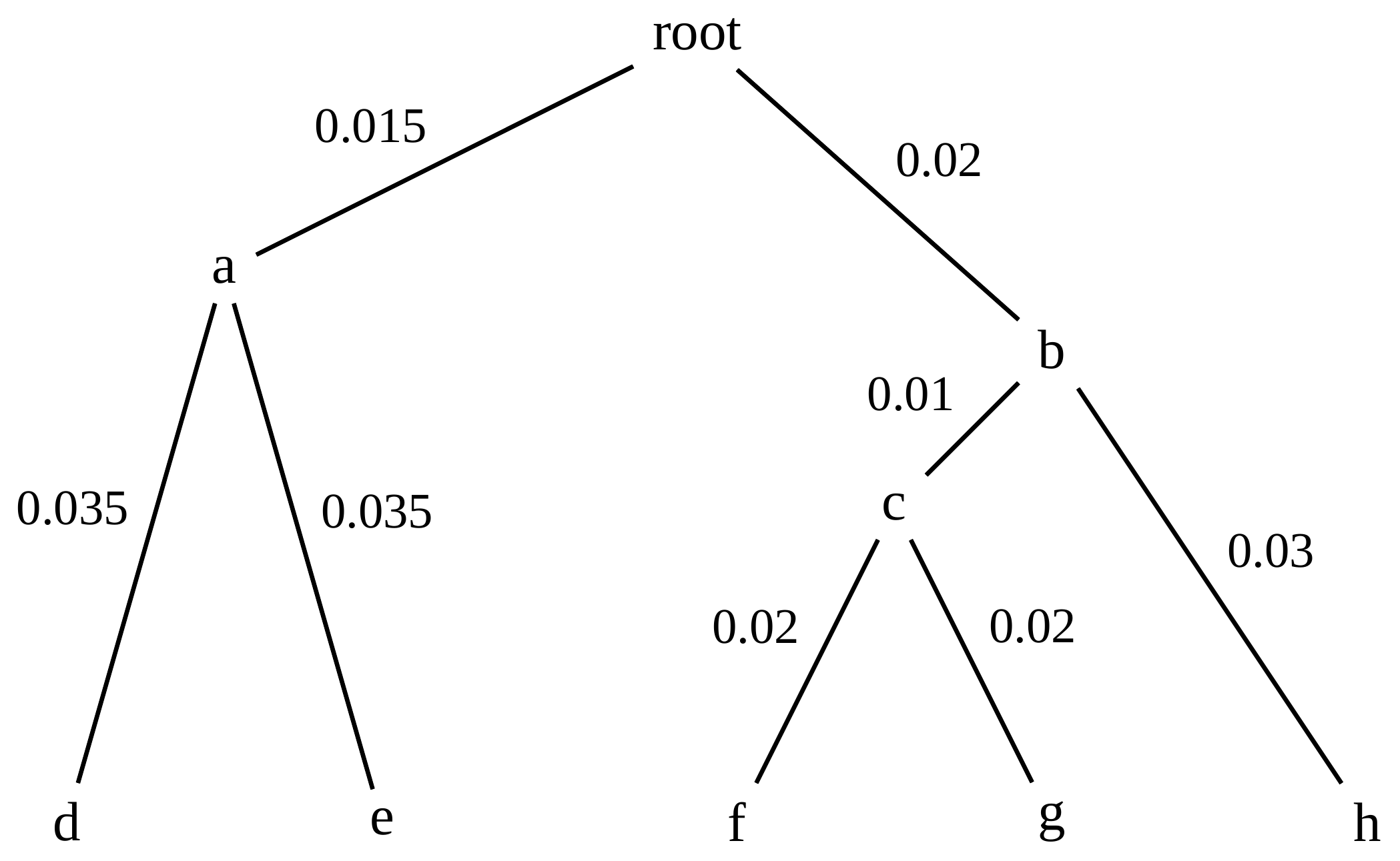

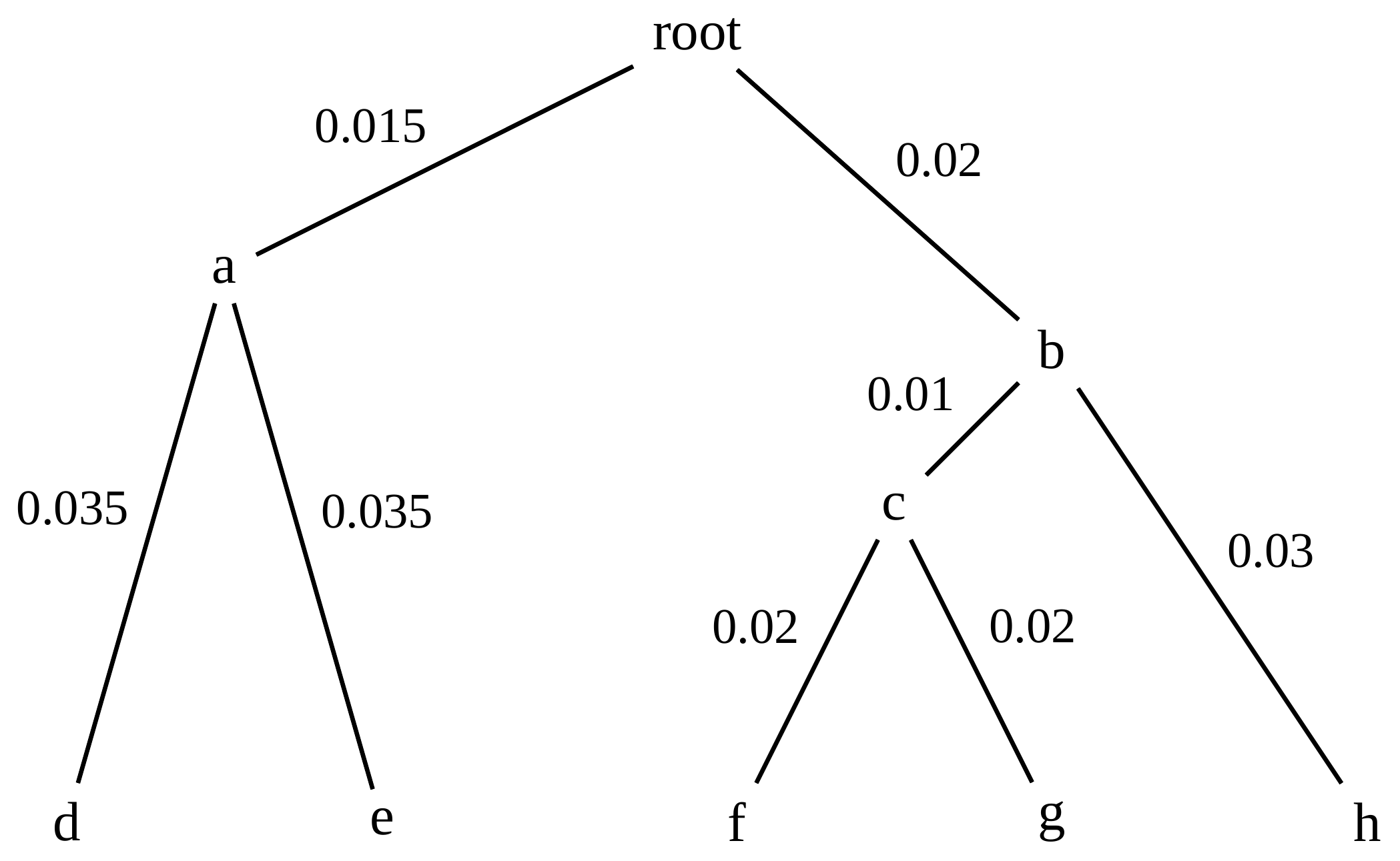

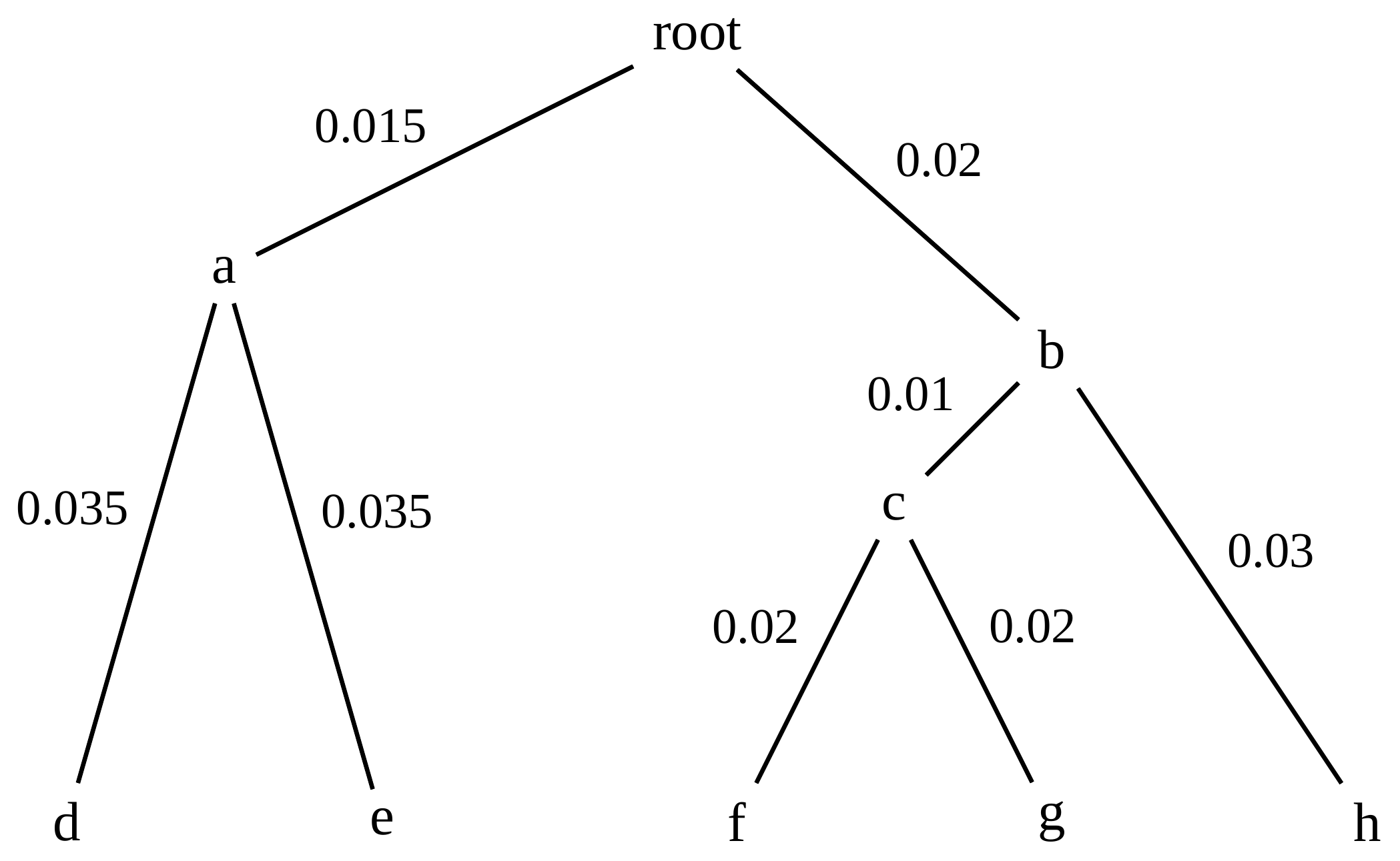

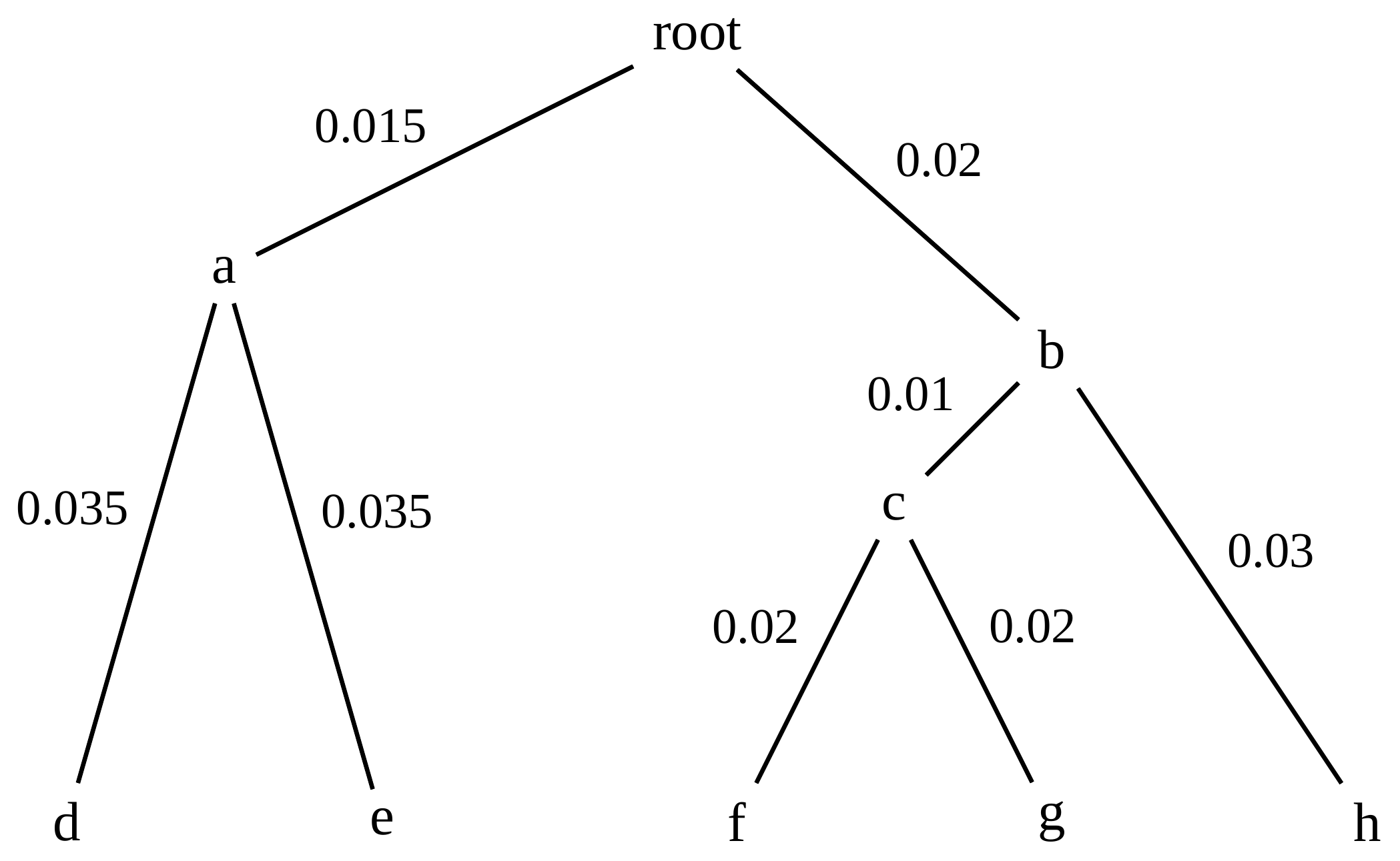

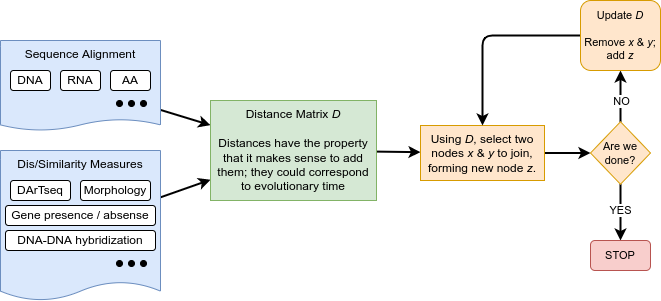

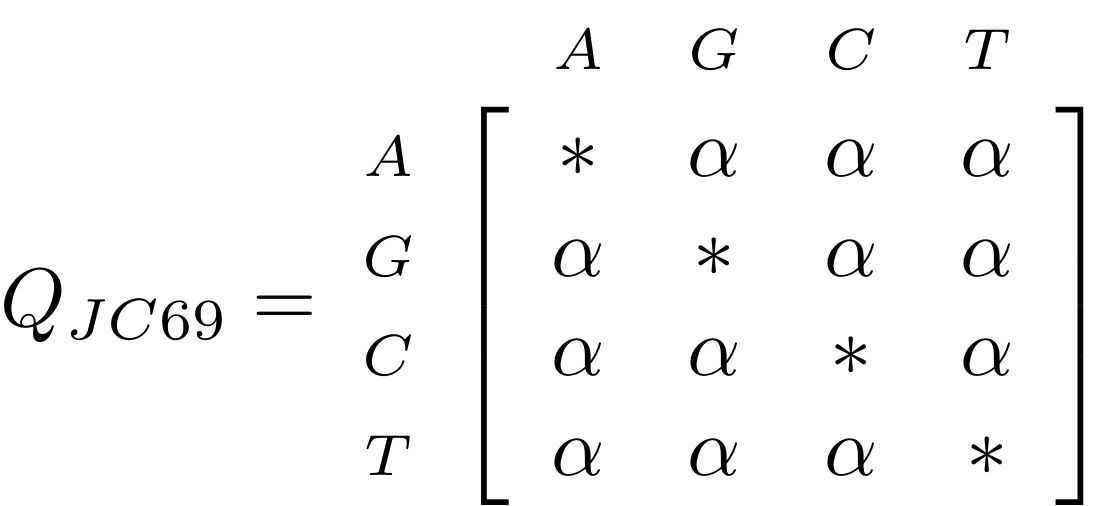

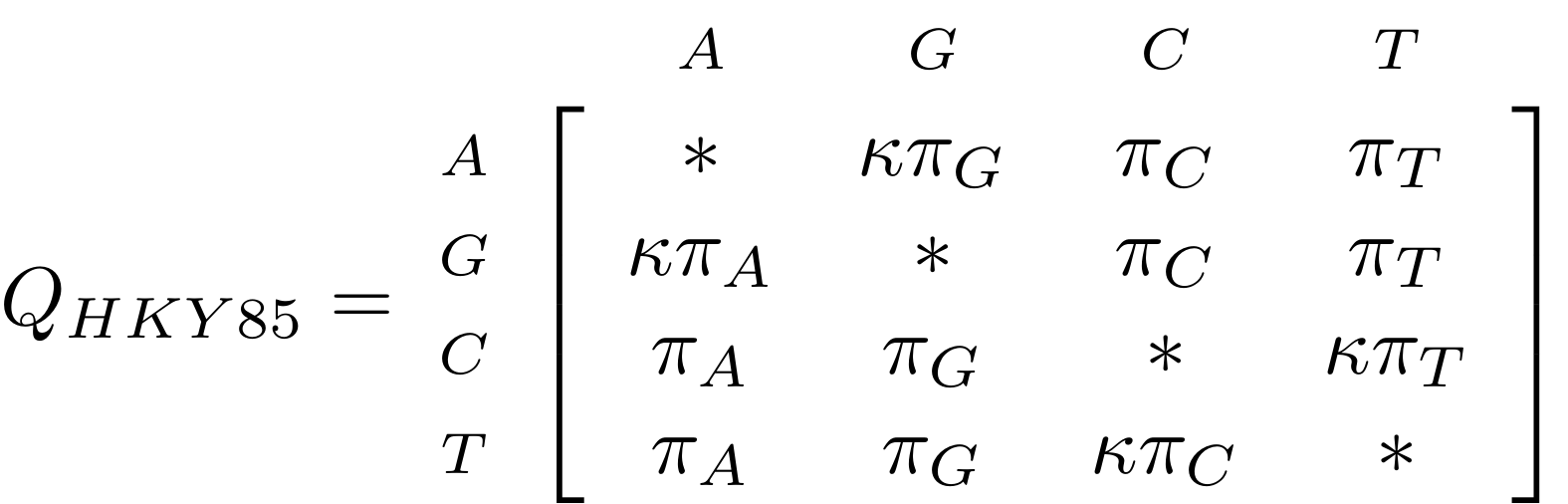

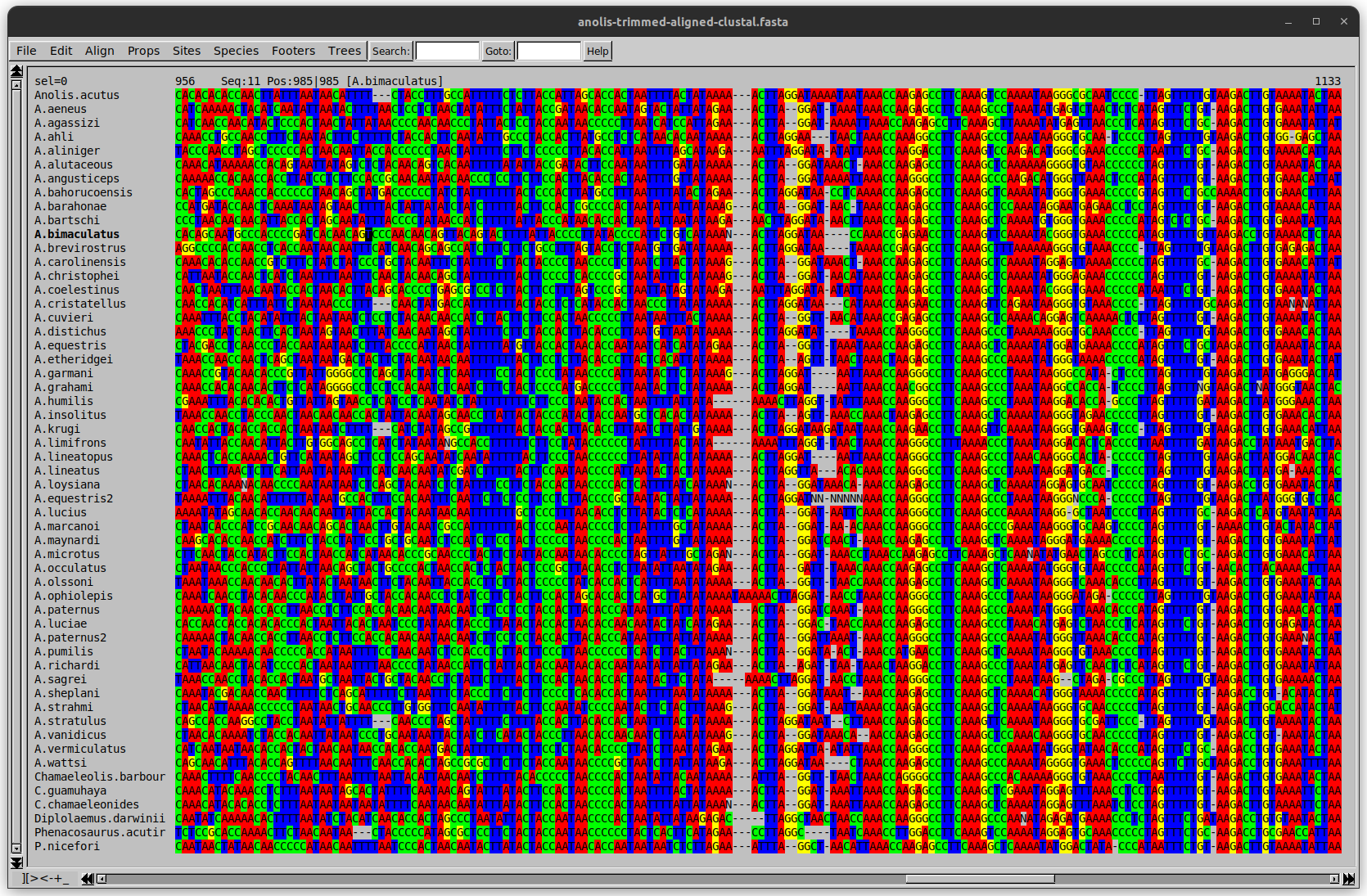

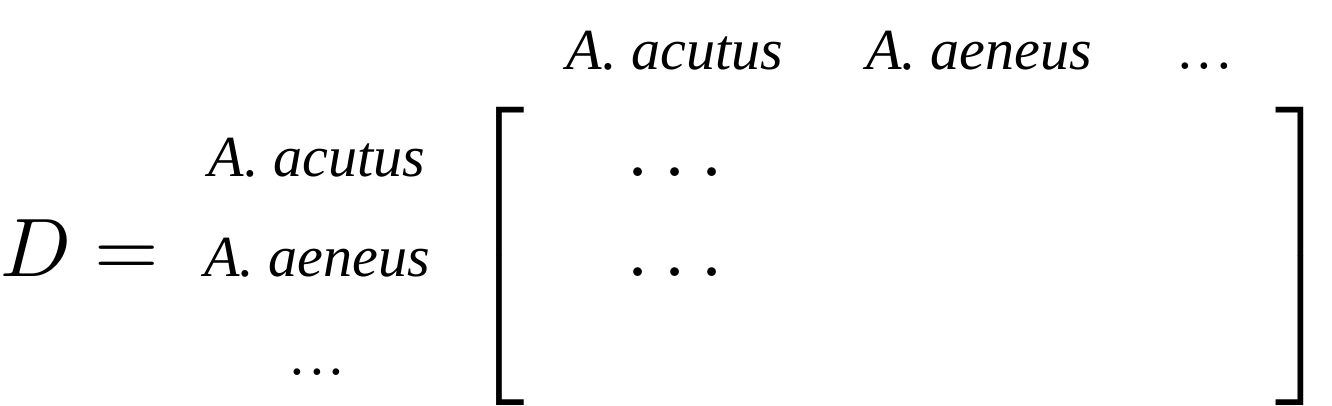

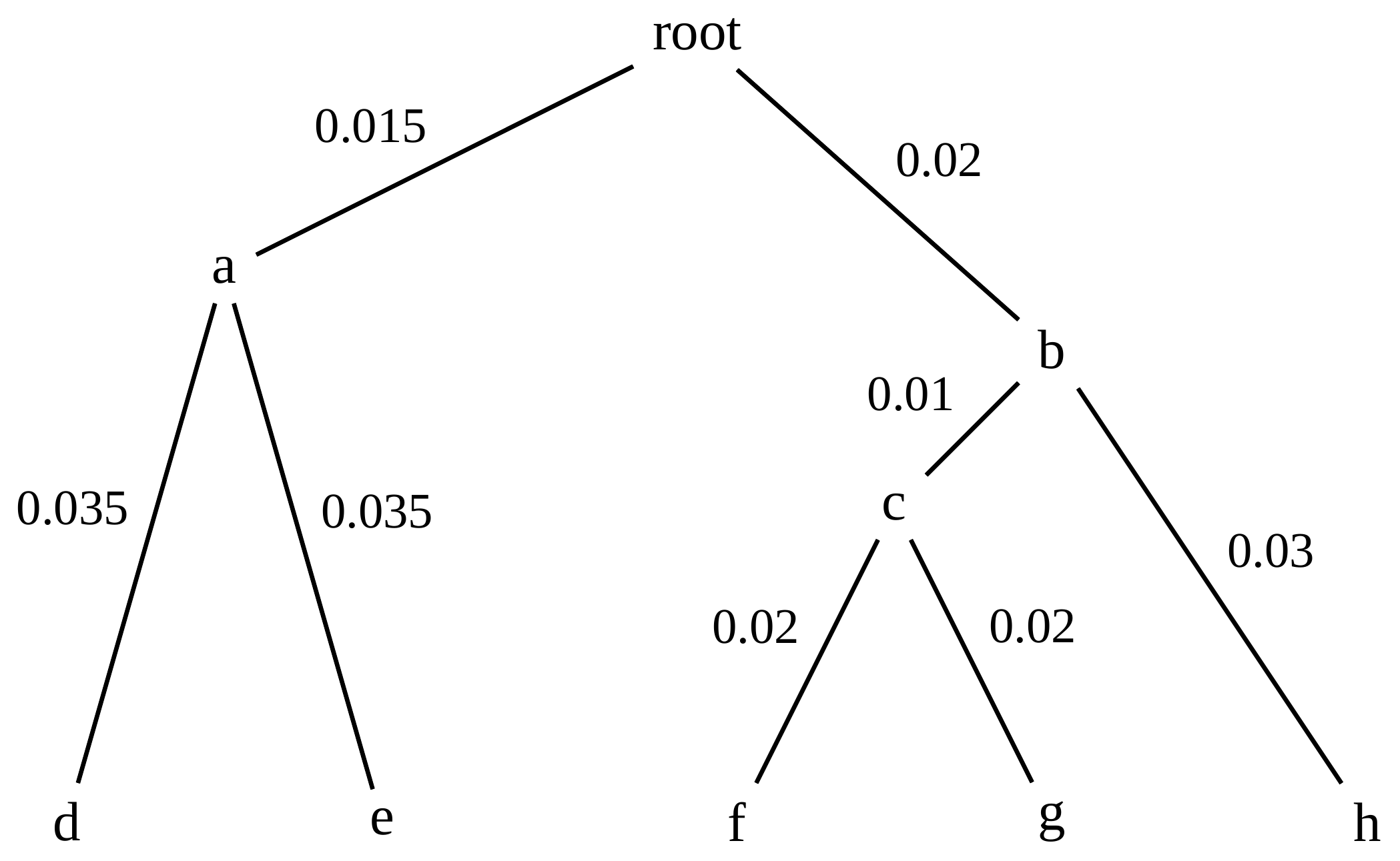

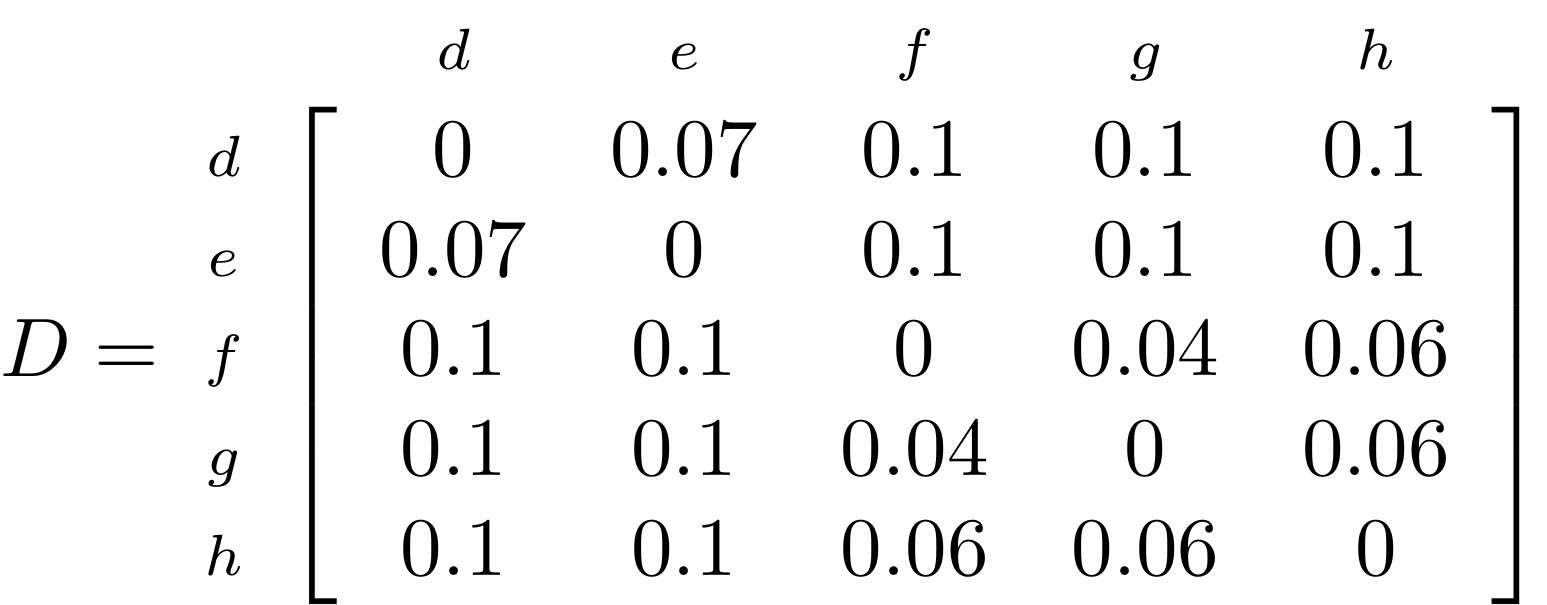

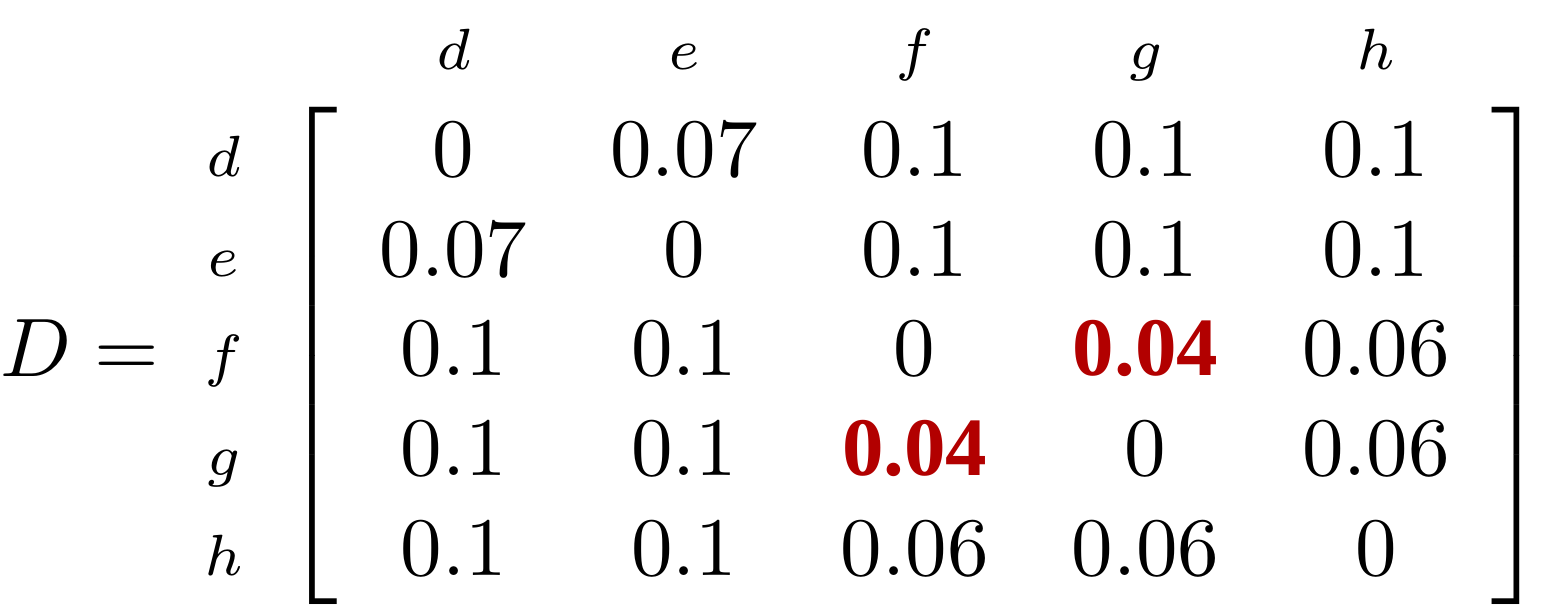

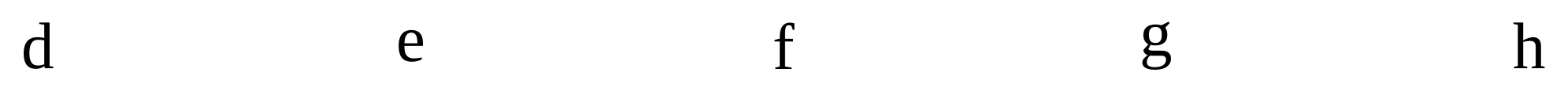

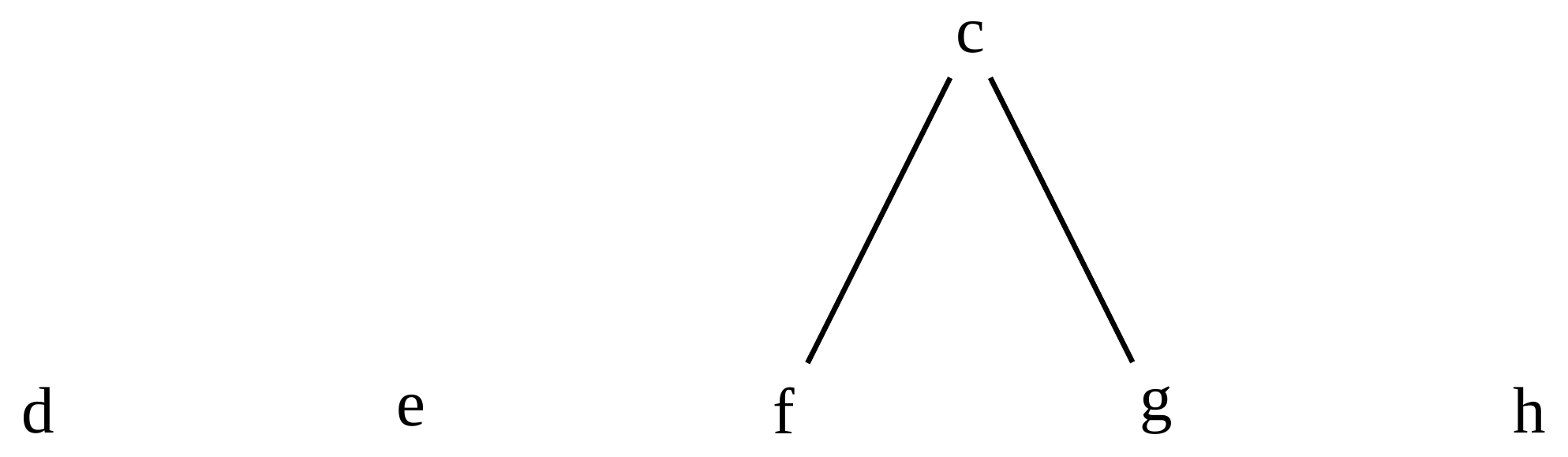

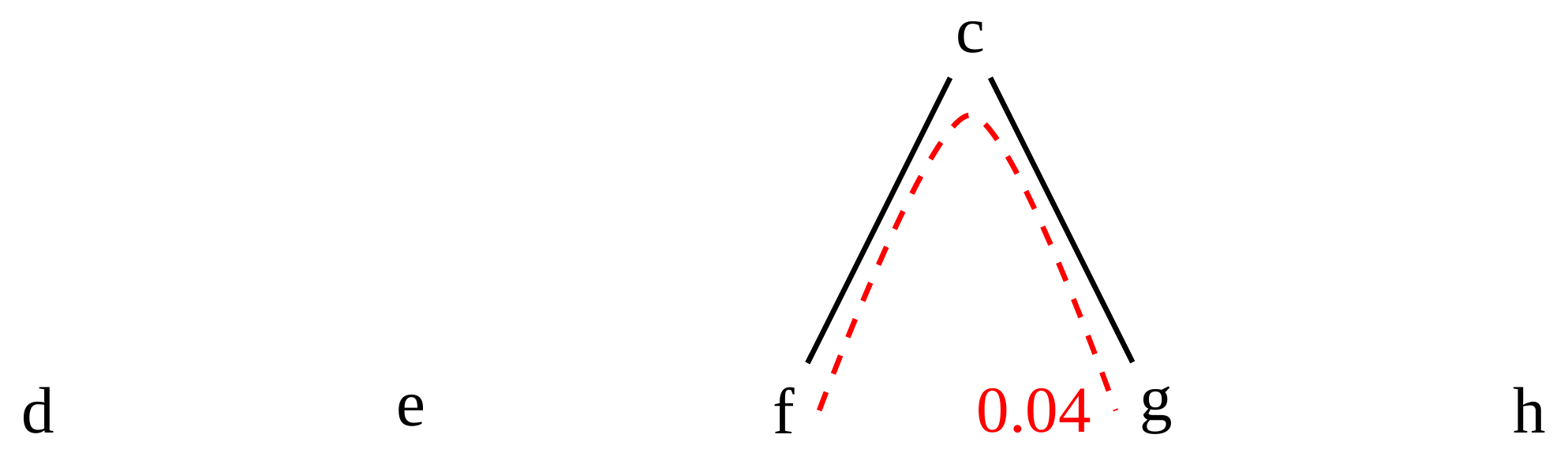

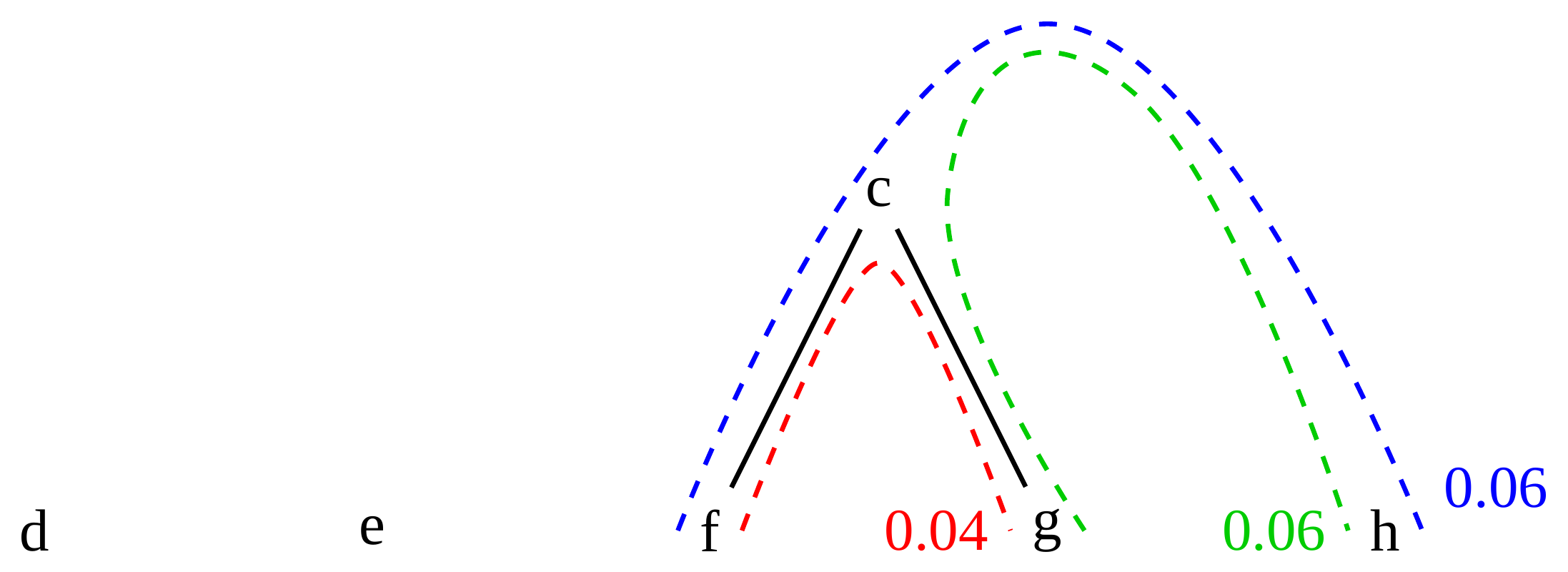

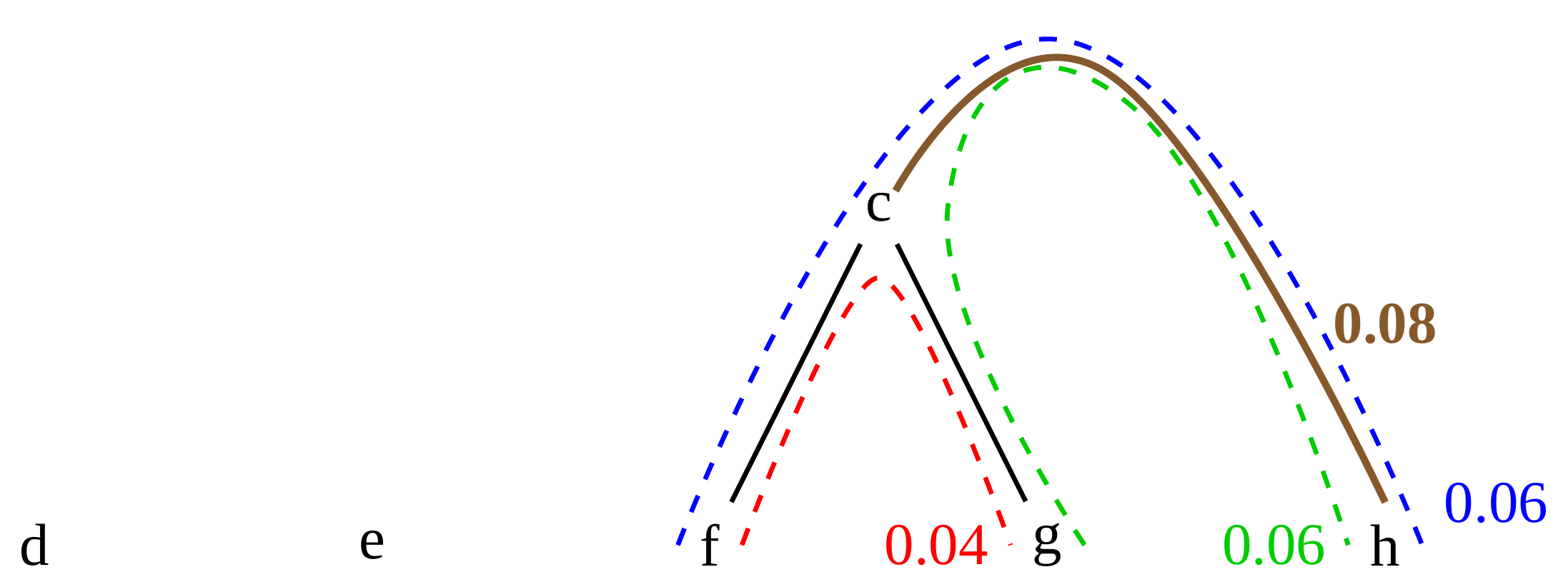

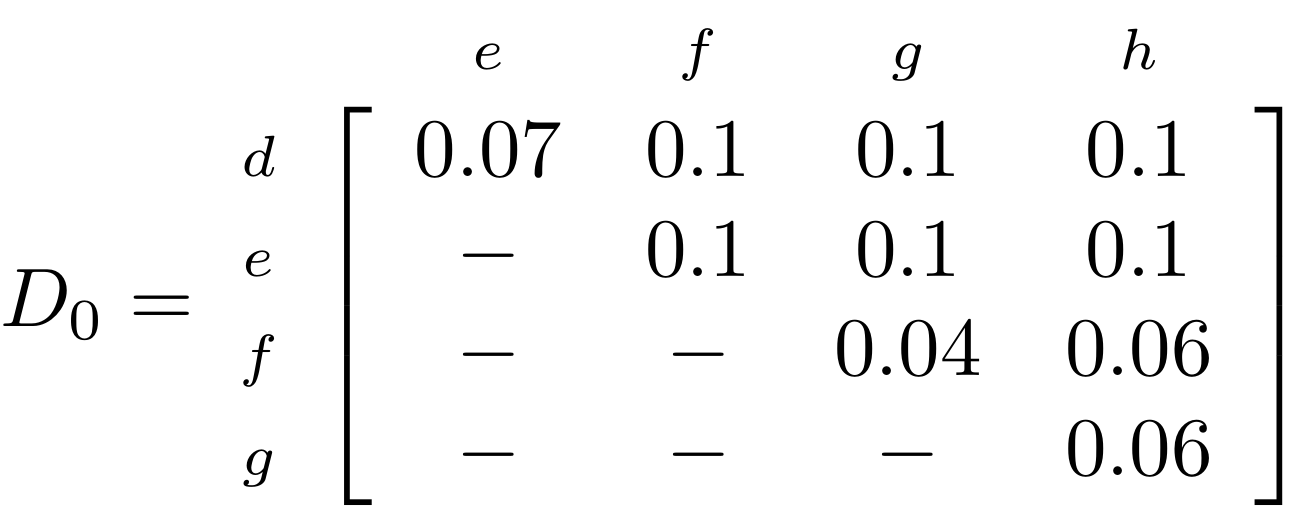

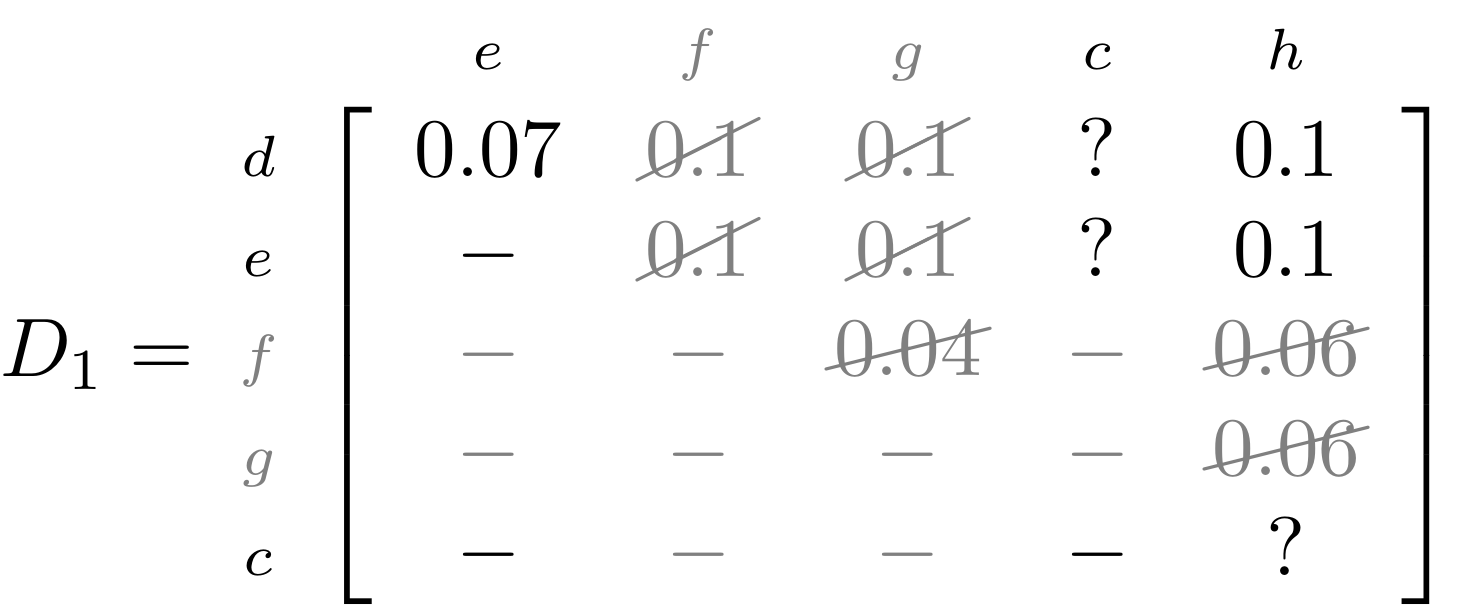

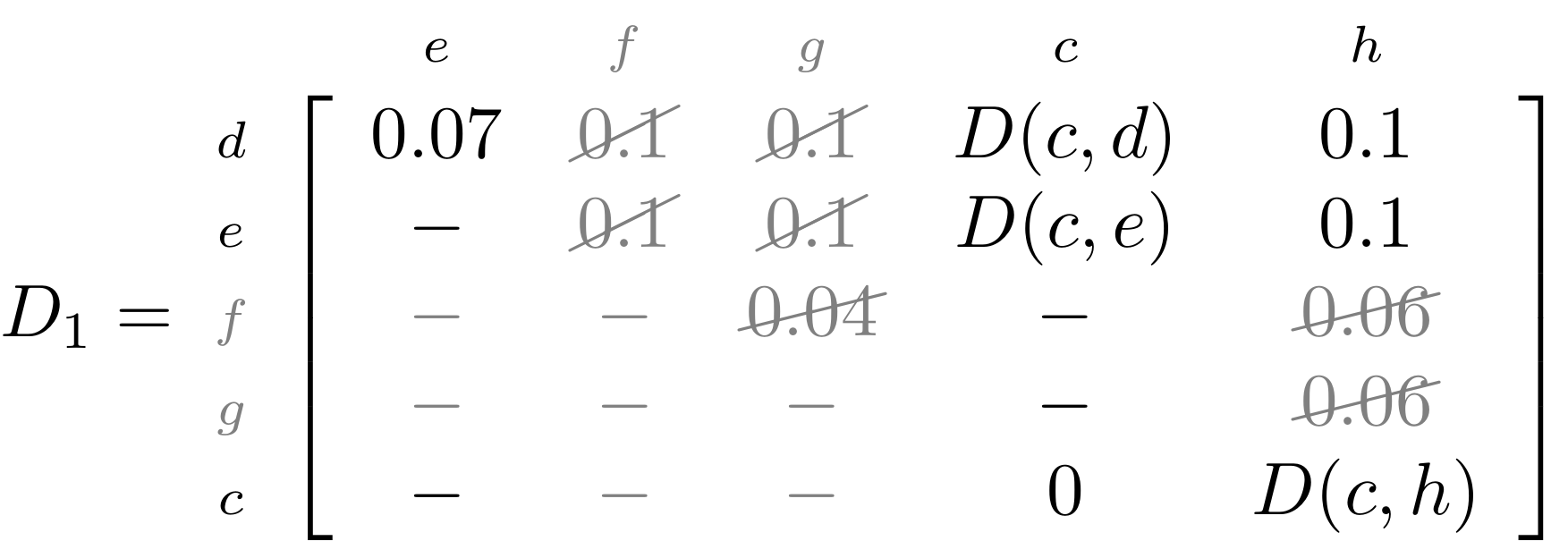

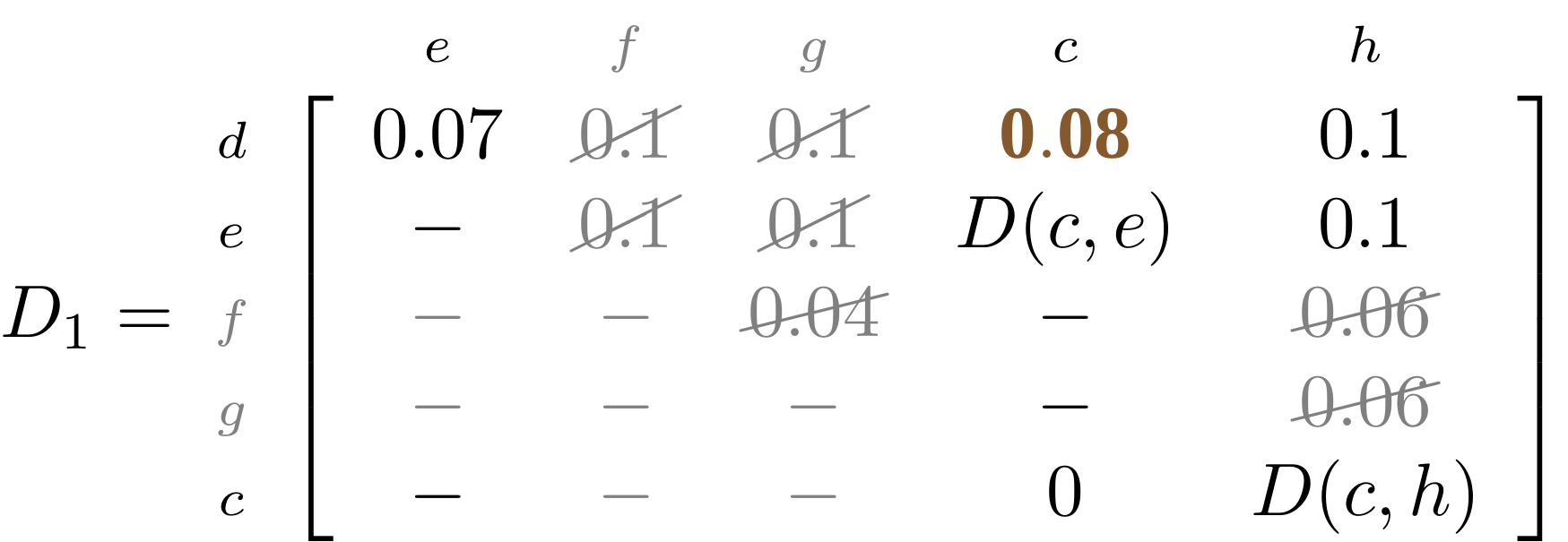

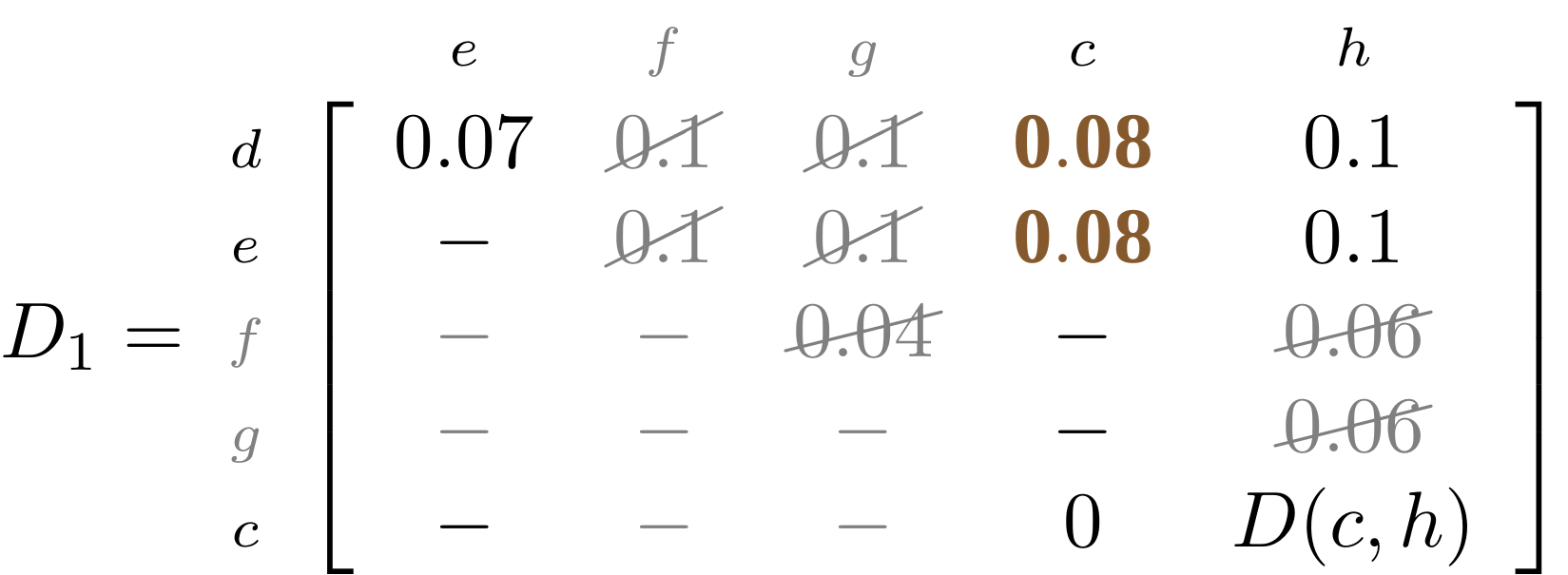

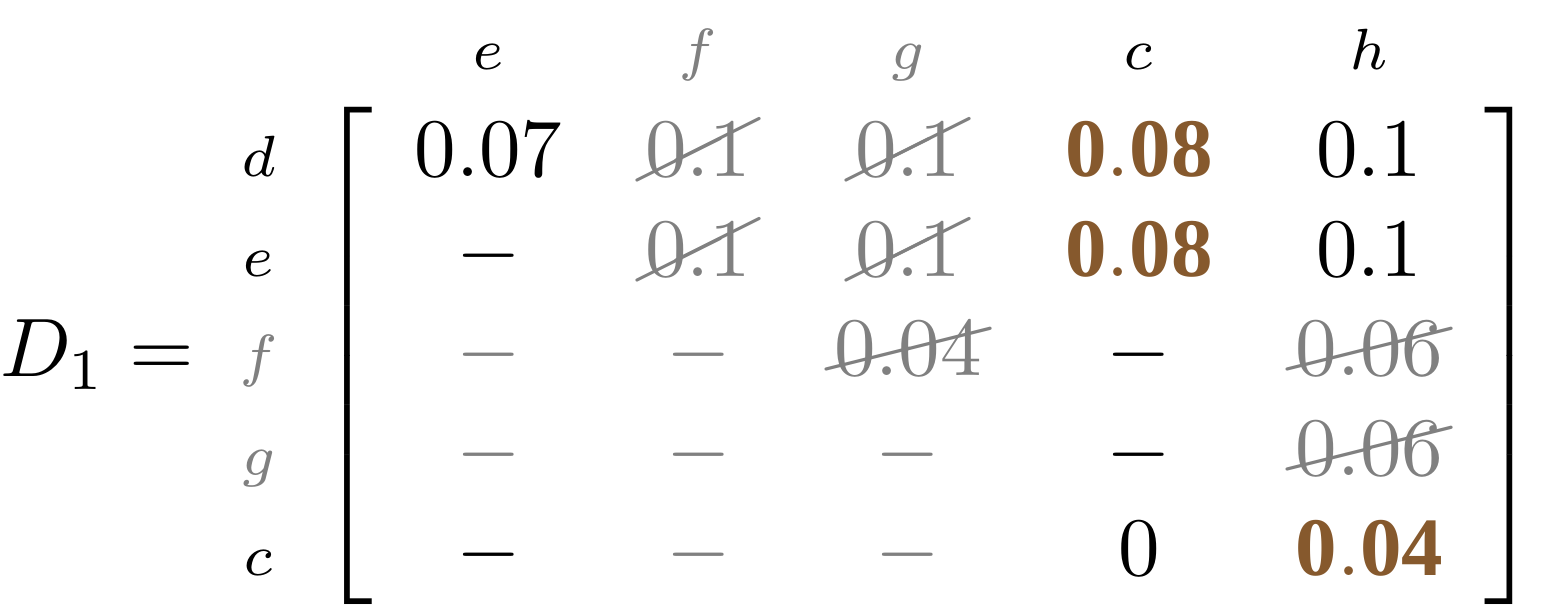

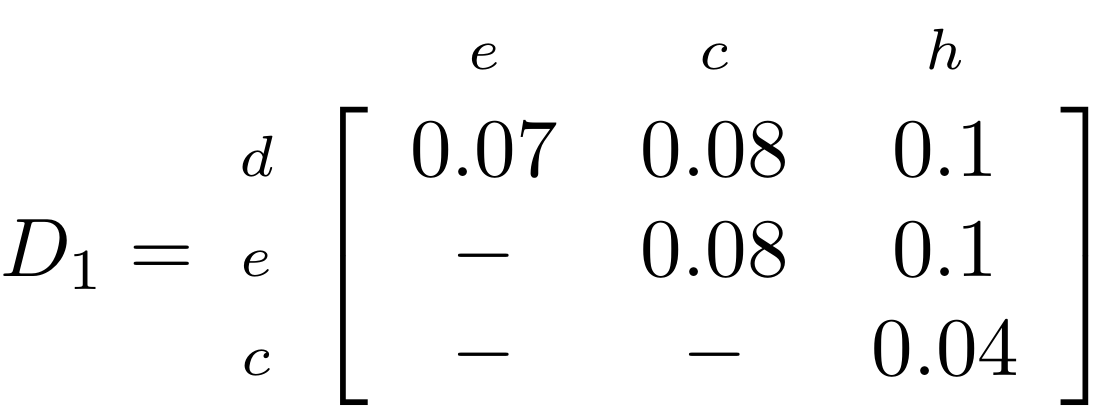

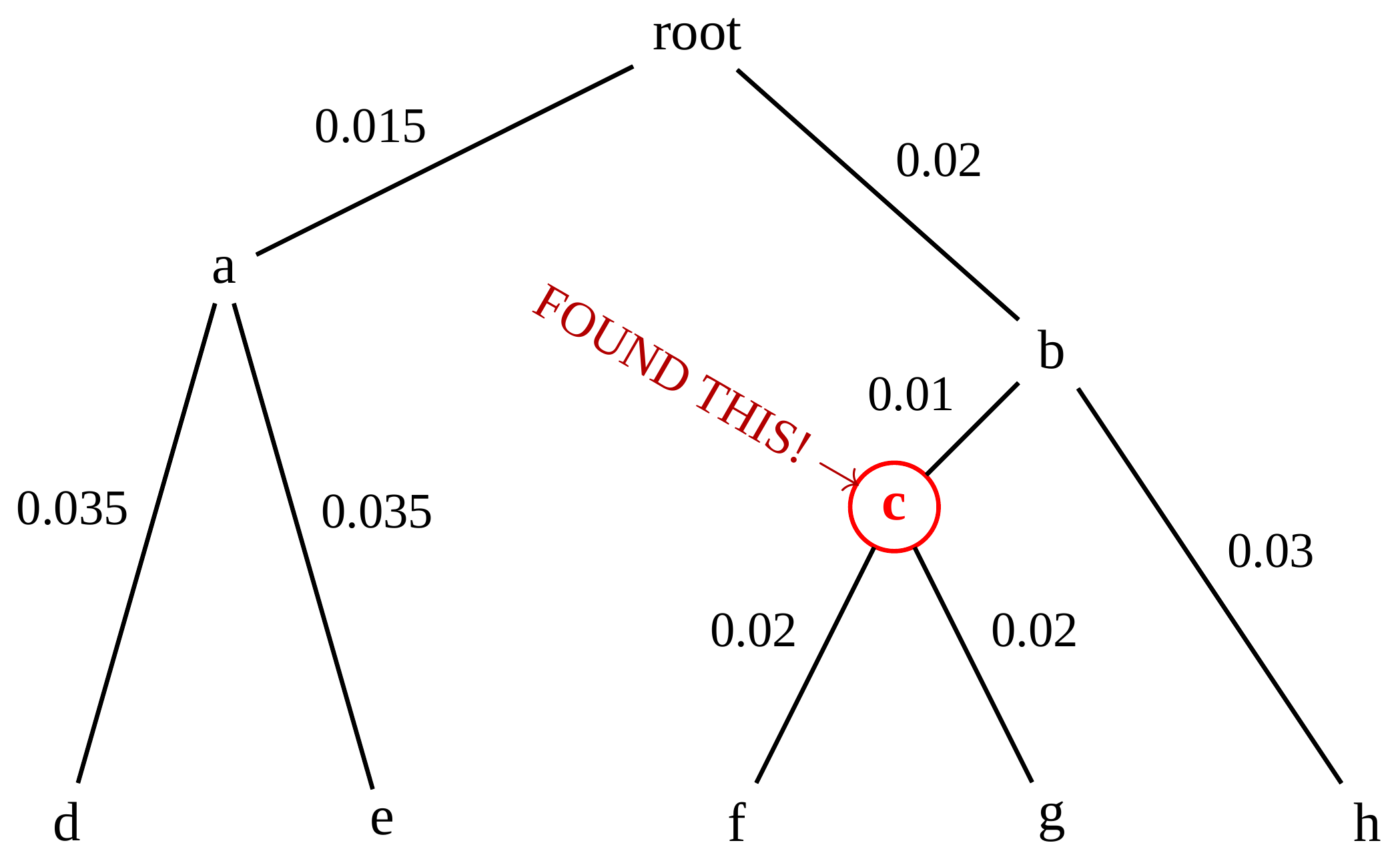

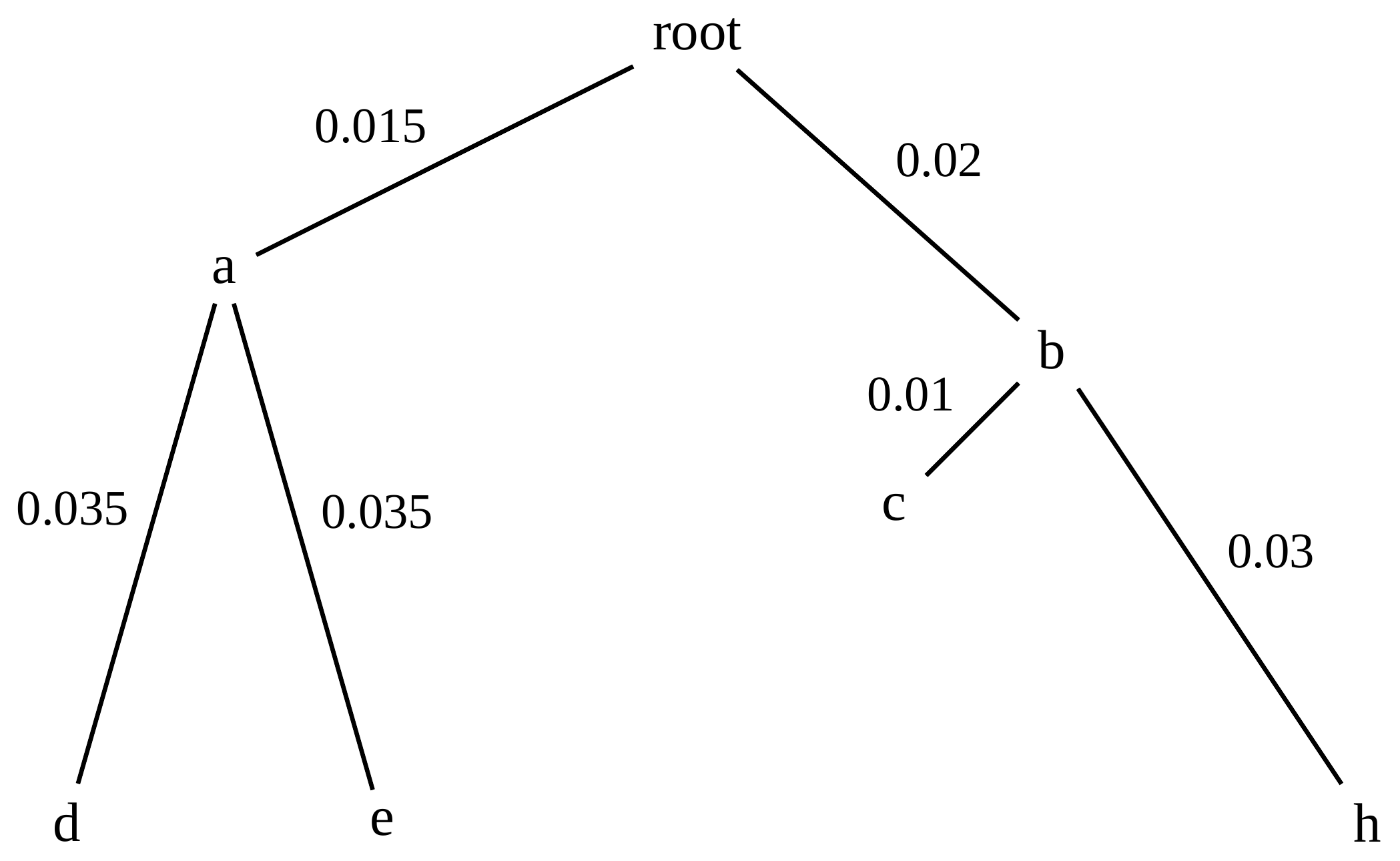

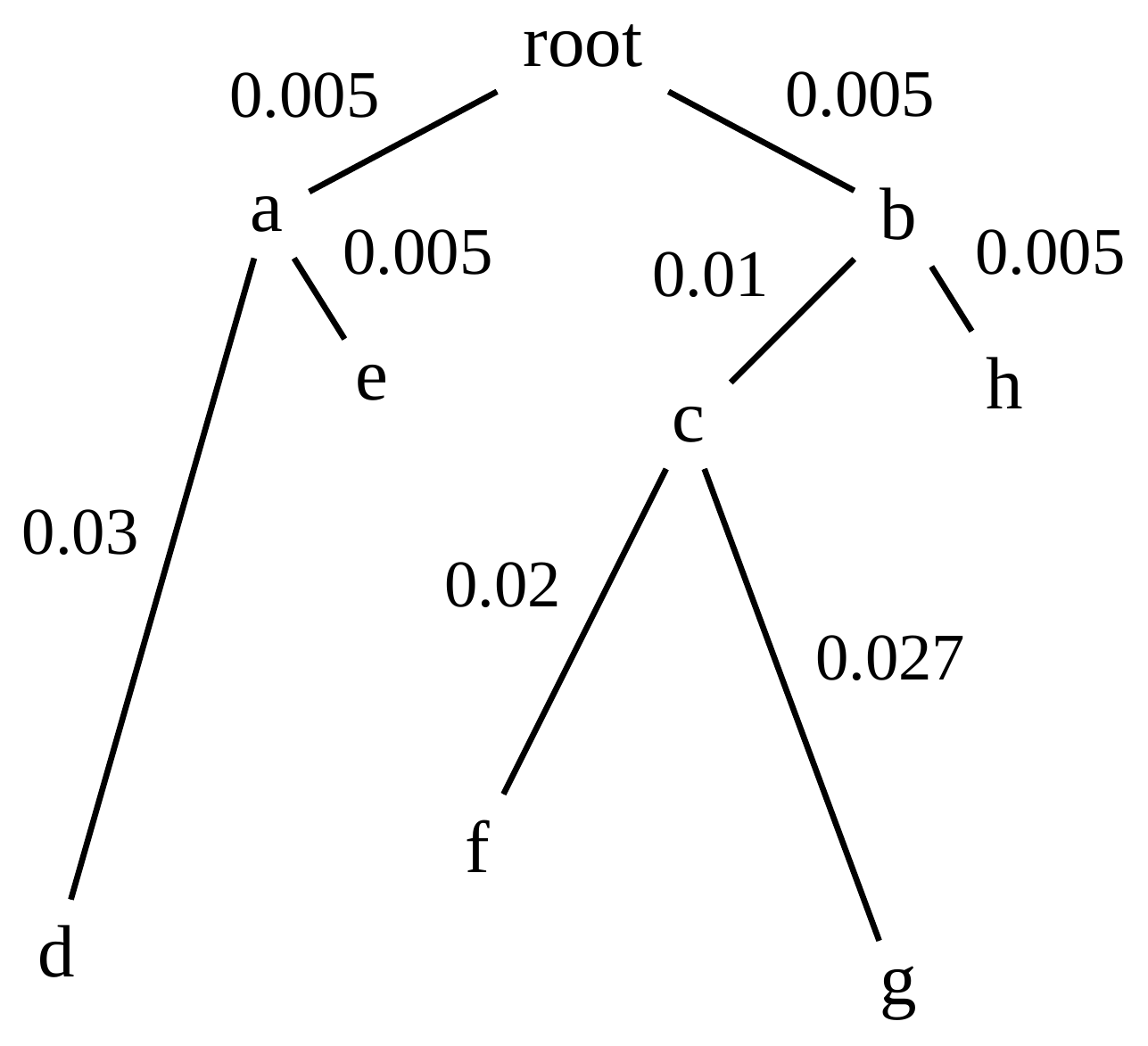

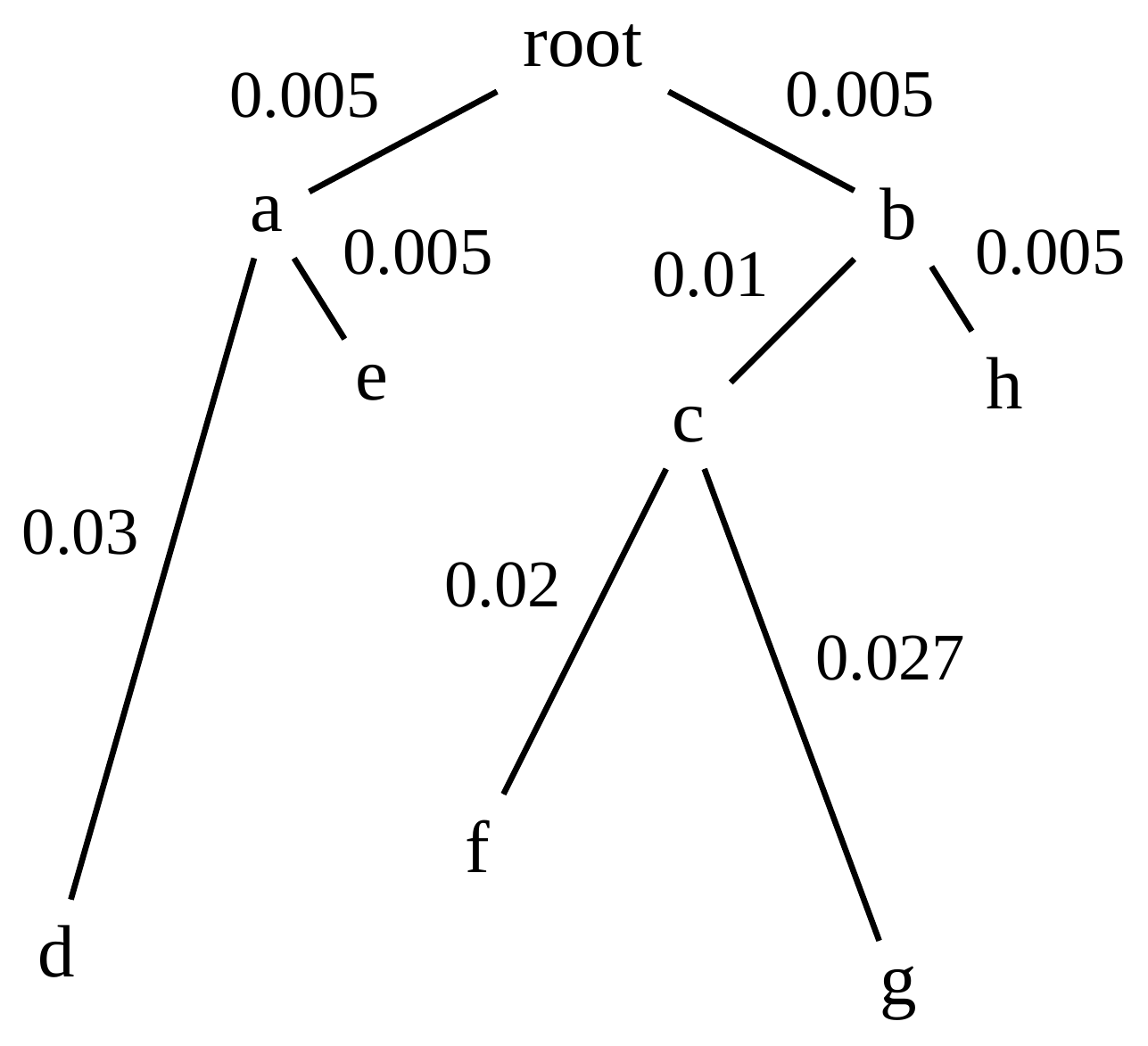

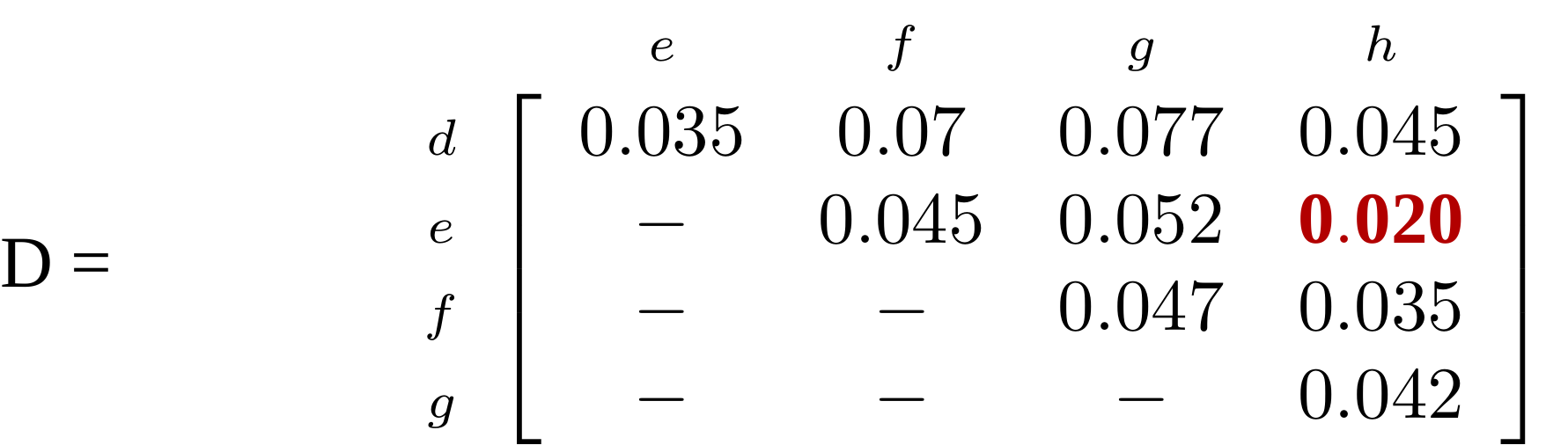

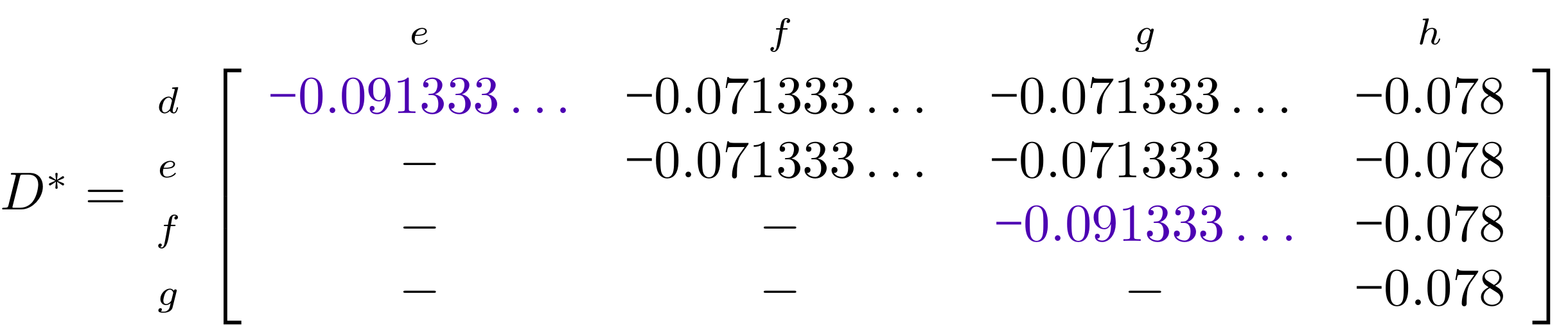

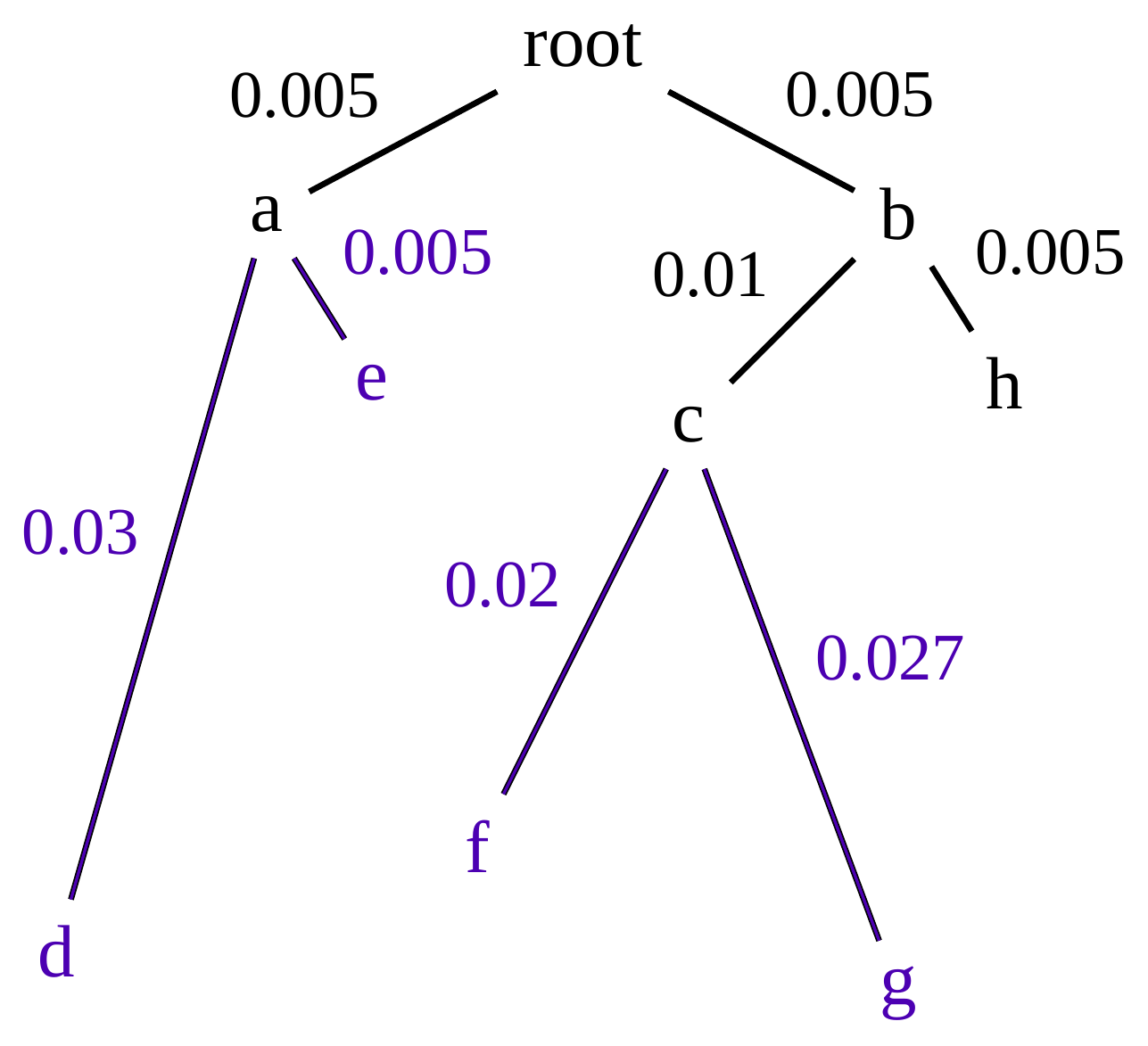

name: inverse layout: true class: center, middle, inverse <div class="my-header"><span> <a href="/training-material/topics/evolution" title="Return to topic page" ><i class="fa fa-level-up" aria-hidden="true"></i></a> <a href="https://github.com/galaxyproject/training-material/edit/main/topics/evolution/tutorials/abc_intro_phylo-trees/slides.html"><i class="fa fa-pencil" aria-hidden="true"></i></a> </span></div> <div class="my-footer"><span> <img src="/training-material/shared/images/biocommons-utas.png" alt="page logo" style="height: 40px;"/> </span></div> --- <img src="/training-material/shared/images/biocommons-utas.png" alt="page logo" class="cover-logo" /> <br/> <br/> # Phylogenetics - Back to Basics - Building Trees <br/> <br/> <div markdown="0"> <div class="contributors-line"> <ul class="text-list"> <li> <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/mcharleston/" class="contributor-badge contributor-mcharleston"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/mcharleston?s=36" alt="Michael Charleston avatar" width="36" class="avatar" /> Michael Charleston</a></li> </ul> </div> </div> <!-- modified date --> <div class="footnote" style="bottom: 8em;"> <i class="far fa-calendar" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="visually-hidden">last_modification</span> Updated: <i class="fas fa-fingerprint" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="visually-hidden">purl</span><abbr title="Persistent URL">PURL</abbr>: <a href="https://gxy.io/GTN:S00121">gxy.io/GTN:S00121</a> </div> <!-- other slide formats (video and plain-text) --> <div class="footnote" style="bottom: 5em;"> <i class="fas fa-file-alt" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="visually-hidden">text-document</span><a href="slides-plain.html"> Plain-text slides</a> | </div> <!-- usage tips --> <div class="footnote" style="bottom: 2em;"> <strong>Tip: </strong>press <kbd>P</kbd> to view the presenter notes | <i class="fa fa-arrows" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="visually-hidden">arrow-keys</span> Use arrow keys to move between slides </div> ??? Presenter notes contain extra information which might be useful if you intend to use these slides for teaching. Press `P` again to switch presenter notes off Press `C` to create a new window where the same presentation will be displayed. This window is linked to the main window. Changing slides on one will cause the slide to change on the other. Useful when presenting. --- ## Requirements Before diving into this slide deck, we recommend you to have a look at: - [Introduction to Galaxy Analyses](/training-material/topics/introduction) --- # Why _build_ trees? <br> The main reason we end up building a tree is that searching tree space for an optimal one takes too long when the number of taxa gets large. <br> .reduce70[ | _n_ | # trees | yes, but how much is that _really_? | --- |---|:--| | 3 | 3 | enumerable by hand | | 4 | 15 | enumerable by hand | | 5 | 105 | enumerable by hand on a rainy day | | 6 | 945 | enumerable by computer | | 7 | 10395 | still searchable very quickly on computer | | 8 | 135135 | a bit more than the number of hairs on your head | | 9 | 2027025 | population of Sydney living west of Parramatta | | 10 | 34459425 | \\(\approx\\) upper limit for exhaustive searching; about the number of possible combinations of numbers in the National Lottery | | 20 | $$8.2\times 10^{21}$$ | \\( \approx \\) upper limit for branch-and-bound searching | | 48 | $$ 3.21 \times 10^{70} $$ | \\(\approx\\) number of particles in the universe | | 136 | $$ 2.11 \times 10^{267} $$ | number of trees to choose from in the ``Out of Africa'' data¹ | ] .footnote[ ¹ Vigilant et al., 1991 ] --- # Tree space is worse than "space" space <br>  <br> NGC 2207 and IC 2163 galaxies colliding. <br> .footnote[Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Featured_pictures/Astronomy] --- # Why should building work then? <br> <br> Some parts of a phylogeny can be confidently accepted: when there are two species much more similar to each other than they are to any other species, we can confidently say that they are likely to be each other's closest relatives, in the set of species of interest. <br> <br> If molecular sequences evolve at a nice steady rate - the "molecular clock" hypothesis - and if there's neither too little nor too much change, this can be good enough. --- # Distances from trees <br> <br> Before we talk about building a tree from distances, we need to think about how distances are reflected by trees. <br> <br> The most natural way to infer distances from trees is by adding the lengths of branches between each pair of nodes. <br> <br> Such distances are called *patristic* distances (I don't know why). --- # Patristic Distances <br> <br>  Rooted binary tree with branch lengths --- # Patristic Distances <br> <br>  <br> Patristic distance between tips f and g is 0.02 + 0.025 = 0.045 --- # Patristic Distances <br> <br>  <br> Patristic distance between tips g and h is 0.025 + 0.01 + 0.035 = 0.07 --- # Patristic Distances <br> <br>  <br> Patristic distance between tips e and f is 0.02 + 0.015 + 0.02 + 0.01 + 0.02 = 0.085 --- # Tree-like distances are easy <br> <br> A set of distances between the tips (taxa) that match the patristic distances of some tree is called **tree-like**. <br> <br> Given tree-like distances, most tree construction methods will work. <br> <br> Yes, _most_ - not all! --- # Clock-like <br> <br> The easiest possible distance data to work with are those where the distance from the root to every tip is the same. <br> <br> Such trees (and the distances derived from them) are called _ultrametric_ (that is, they have the same root-to-tip distance for every tip). --- # Clock-like <br> <br> For example, suppose this is the _true_ tree relating some species of interest, with actual branch lengths as labelled: <br> <br>  --- # These distances are _ultrametric_ <br> .pull-left[ .image-90[  ] ] .pull.right[ * The maximum root-to-tip distance is called the _height_ of the tree. * Here, the root-to-tip distances are all the same. A set of distances with this property is called _ultrametric_. * If the distances represent evolutionary time accurately and all the tips are in the present, then we should expect this property. * Reconstructing trees from ultrametric distances is _super easy_. ] --- # These distances are _ultrametric_ <br> <br> .left-column40[  ] .right-column60[ Distance matrix: .center[ | | d | e | f | g | h | |:---:|:---:|:---:|:---:|:---:|:---:| |**d** | 0 | 0.07 | 0.1\* | 0.1 | 0.1 | |**e** | 0.07 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |**f** | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |**g** | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.06 | |**h** | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0 | ] .reduce70[\* Note; this is twice the root-to-tip distance.] ] .pull-bottom[ Any ultrametric tree satisfies the three-point condition (for rooted trees): for any three tips x, y, z, the larger two pairwise distances of D(x, y), D(x,z), D(y,z) will be equal. ] --- # These distances are _ultrametric_ <br> <br> .left-column40[  ] .right-column60[ Distance matrix: .center[ | | d | e | f | g | h | |:---:|:---:|:---:|:---:|:---:|:---:| |**d** | 0 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |**e** | - | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |**f** | - | - | 0 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |**g** | - | - | - | 0 | 0.06 | |**h** | - | - | - | - | 0 | ] <br> Since this is a symmetric matrix we usually just show half of it... ] --- # These distances are _ultrametric_ <br> <br> .left-column40[  ] .right-column60[ Distance matrix: .center[ | | e | f | g | h | |:---:|:---:|:---:|:---:|:---:|:---:| |**d** | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |**e** | - | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |**f** | - | - | 0.04 | 0.06 | |**g** | - | - | - | 0.06 | ] <br> ... and only the non-zero entries. ] --- # The general approach <br> <br>  --- # Our distances <br> <br> * We get distances from molecular sequences once they have been _aligned_. * There are various ways to compare aligned sequences to obtain distances: - uncorrected "p-distance" -- the proportion of sites that differ between the two sequences; - the Jukes-Cantor (JC69) correction, which takes into account of multiple character state changes through time; - The Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano (HKY85) model, which also allows for variation in nucleotide frequencies \\(\pi\_{A}, \pi\_{C}, \pi\_{G}, \pi\_{T}\\) as well as different transition/transversion rates; - and more. --- # Jukes-Cantor / JC69 <br> This model has one single parameter, assuming that the base frequencies are each 25%: \\(\pi\_{A}=\pi\_{G}=\pi\_{C}=\pi\_{T}=0.25\\) <br> <br> The rate matrix looks like this: <br> .image-40[  ] <br> .reduce50[where the asterisk is a short-hand to make the row-sums equal 0.] <br> <br> Under this model the expected number of substitutions between two sequences with a p-distance of \\(p\\) is $$\hat{d} = \frac{-3}{4}\ln\left(1-\frac{4}{3}p\right)$$ --- # Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano / HKY85 <br> This model allows for variation in nucleotide frequencies \\(\pi\_{A}, \pi\_{G}, \pi\_{C}, \pi\_{T}\\) as well as different transition/transversion rates using parameter \\(\kappa\\): <br> <br> .image-40[  ] <br> <br> This model also allows for a correction to turn relative observed numbers of substitutions between the different bases into expected total number of substitutions between two sequences, but it is much more complex. --- # From alignment to distances <br> <br> .left-column50[  ] .right-column50[  <br> <br> Once the alignment is complete, each pair of sequences is compared to give an estimated distance between them: this forms the distance matrix for tree building. ] --- # Example <br> <br> _Ultrametric distances_ --- # The true tree <br> <br>  --- # Original Distance Matrix <br> <br>  --- # Original Distance Matrix <br> <br>  --- <br> <br> <br> <br> <br>  ---  --- <br> <br> <br> <br> <br>  <br> <br> The distance between f and g *D(f,g)* is the sum of the branch lengths on the path between them. --- <br> <br> <br> <br> <br>  <br> <br> Similarly the distances *D(f,h)* and *D(g,h)* are the sum of branch lengths. --- <br> <br> <br> <br>  <br> <br> Therefore: <br> $$\mathbf{D(c,h)} = \frac{D(f,h)+D(g,h)-D(f,g)}{2}$$ --- # Forming the next Distance Matrix <br> <br> We need to remove columns and rows f and g, and add new column and row c. .image-75[  ] --- # Forming the next Distance Matrix <br> <br> The entries for *D(f,d), D(g,d)* etc get dropped. .image-75[  ] --- # Forming the next Distance Matrix <br> <br> We fill in the new entries using the formulae below: .image-75[  ] <br> <br> $$D(c,d) = \frac{1}{2}(D(f,d)+D(g,d)-D(f,g)) = \frac{1}{2}(0.1+0.1-0.04) = \mathbf{0.08}$$ --- # Forming the next Distance Matrix <br> <br> We fill in the new entries using the formulae below: .image-75[  ] <br> <br> $$D(c,e) = \frac{1}{2}(D(f,e)+D(g,e)-D(f,g)) = \frac{1}{2}(0.1+0.1-0.04) = \mathbf{0.08}$$ --- # Forming the next Distance Matrix <br> <br> We fill in the new entries using the formulae below: .image-75[  ] <br> <br> $$D(c,h) = \frac{1}{2}(D(f,h)+D(g,h)-D(f,g)) = \frac{1}{2}(0.06+0.06-0.04) = \mathbf{0.04}$$ --- # Forming the next Distance Matrix <br> <br> .image-75[  ] --- # Forming the next Distance Matrix <br> <br> Completed new distance matrix: .image-50[  ] ---  ---  Now we have reduced the problem by one taxon / sequence: we repeat until we have just two more taxa to join and that will give us the root! --- # Non-clocklike trees <br> <br> *Losing the ultrametric property* --- # Not perfectly clock-like <br> <br> Now suppose this is the _true_ tree relating some species of interest, with actual branch lengths as labelled: <br> <br>  --- <br> <br> .left-column40[  ] .right-column60[ .image-75[  ] <br> The smallest distance doesn't match a true pair of siblings. ] --- # Neighbo[u]r-Joining <br> <br> Neighbo[u]r-Joining solves this problem by accounting for the *net divergence* of node from the rest, so if distances are tree-like, even if they're not ultrametric, it *will* get the tree right. <br> <br> The formula for net divergence, with *n* taxa (i.e., an *n* *x* *n* distance matrix) is <br> <br> $$r\_{i} = \frac{1}{n-2}\sum\_{j\neq i}D(i,j)$$ <br> <br> And the adjusted distance becomes <br> <br> $$D^{\ast}(i,j) = D(i,j) - r(i) - r(j)$$ --- # Adjusted distance matrix <br> Net divergences: .center[ | $$i$$ | $$r(i)$$ | |:---:|:------:| | d | 0.075666 | | e | 0.050666 | | f | 0.065666 | | g | 0.072666 | | h | 0.047333 | ] <br> Adjusted Distances: <br> .image-50[  ] ---  --- #Realistic data <br> <br> *Losing tree-like distances* --- * Real data are not tree-like in general. * We should adjust the final branch lengths that are found. * One criterion is _Minimum Evolution_; this minimises the sum of squared differences ("ordinary least squares"; OLS) between the patristic distances, say _G_, from the tree and the original distances _D_: <br> $$OLS = \sum\_{i,j}(D(i,j) - G(i,j))^{2}$$ <br> This assumes that the estimates are independent of each other, which clearly isn't the case as the distances between tips in the tree often share parts of the paths between them. <br> <br> .reduce70[ Further reading: Denis and Gascuel: doi.org/10.1016/S0166-218X(02)00285-8. ] --- # _Anolis_ tree with uncorrected p-distances <br> <br>  --- # _Anolis_ tree with JC69 distances <br> <br>  --- # _Anolis_ tree with HKY85 distances <br> <br>  --- # Limitations <br> <br> * A tree-building method will _always give you a tree_, even if the data didn't come from one. * There is no information on "next best" trees. * There is no measure of "goodness" for the most part (though you could always quote the least squares error). * Lastly, there is by default no going back on bad decisions: because NJ is a greedy heuristic, once the tree is finished, we _stop_. Luckily, we have programs like FastTree to do some adjustment! --- #Thank you! <br> <br> _Next - estimating trees from alignments_ --- --- ## Thank You! This material is the result of a collaborative work. Thanks to the [Galaxy Training Network](https://training.galaxyproject.org) and all the contributors! <div markdown="0"> <div class="contributors-line"> <table class="contributions"> <tr> <td><abbr title="These people wrote the bulk of the tutorial, they may have done the analysis, built the workflow, and wrote the text themselves.">Author(s)</abbr></td> <td> <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/mcharleston/" class="contributor-badge contributor-mcharleston"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/mcharleston?s=36" alt="Michael Charleston avatar" width="36" class="avatar" /> Michael Charleston</a> </td> </tr> <tr class="reviewers"> <td><abbr title="These people reviewed this material for accuracy and correctness">Reviewers</abbr></td> <td> <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/hexylena/" class="contributor-badge contributor-badge-small contributor-hexylena"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/hexylena?s=36" alt="Helena Rasche avatar" width="36" class="avatar" /></a><a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/burkemlou/" class="contributor-badge contributor-badge-small contributor-burkemlou"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/burkemlou?s=36" alt="Melissa Burke avatar" width="36" class="avatar" /></a><a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/shiltemann/" class="contributor-badge contributor-badge-small contributor-shiltemann"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/shiltemann?s=36" alt="Saskia Hiltemann avatar" width="36" class="avatar" /></a></td> </tr> </table> </div> </div> <div style="display: flex;flex-direction: row;align-items: center;justify-content: center;"> <img src="/training-material/shared/images/biocommons-utas.png" alt="page logo" style="height: 100px;"/> </div> Tutorial Content is licensed under <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/">Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License</a>.<br/>